1. I refer to the exhibition held when Kim Hong-Hee was the director of the Seoul Museum of Art: X: Korean Art in the 1990s (12 December 2016-19 February 2017, Seoul Museum of Art Seosomun Main Branch).

2. The prior studies that will be discussed later generally agree with this sentiment.

3. “Women’s art” remains a controversial term in the Korean art community with regards to defining the relationship between feminism and visual art. Patjis on Parade stated that it intended for “women’s art” to acquire a meaning beyond art by women, but it appeared to call attention to feminist art and describe its emergence as that of art “by women,”, without a concrete definition of “women’s art.”

4. Kim Hong-hee, Women and Art (Seoul: Noonbit, 2003)

5. Kim Hyeonjoo, “The History of Feminist Studies in Korean Contemporary Art History,” Art History Forum no. 50 (2020): 60.

6. I refer to the following: Yang Eunhee, “Curators as Cultural Mediators: the Gwangju Biennial in the Context of Globalization of Korean Art Since the 1990s,” Journal of History of Modern Art (2016): 40.

7. Kim Hong-hee, “Introduction, Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade,” Feminist Artist Network (99 Women's Art Festival Organizing Committee), Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade (Seoul: Hongdesign, 1999), 13.

8. Cho Hyeok, “History of Korean Feminist Art, a Reconstruction of Discourses: The 1980s ‘Yeoseong misul (Women’s Art)’ and the 1990s ‘Postmodern Feminist Art,” Art History Forum, no.51 (2020); Park Sohyun, “Kim Honghee's Feminist/Postmodern Art History and the Historical Status of Lee Bul,” Journal of Korean Modern & Contemporary Art History no. 40 (2020).

9. Cho Hyeok (2020), op.cit., 99.

10. Cho Hyeok(2020), op.cit., 103-5.

11. Park Sohyun (2020), op.cit., 417.

12. I refer to the recent compilation titled Love and Ambition. In the discussion moderated by Lee Jinshil, with participants such as Kim Hyeonjoo and Yang Hyo-sil, Kim Hong-hee likewise questions the term yeoseong misul (women’s art), which describes the activities of artists in the 1980s. To this, the participants agreed with her concerns about the English translation of yeoseong misul, women’s art, which might cause the term to become misunderstood as simply “yeoryu(lady)” or fundamentalist feminist activism. At the same time, they suggest accepting yeoseong misul (women’s art) as historical fact and treating the term as a proper noun: Lee Jinshil, “Chaiwa Banbogui Sigandeul: Hanguk Peminijeum Misurui Eojewa Oneul” [Times of Difference and Repetitions: The Past and Present of Korean Feminist Art], Love and Ambition-The Time Difference of Contemporary Feminist Art (Seoul: Mediabus, 2021), 12-49.

13. Kim Hyeonjoo, “Hangukyeondaemisulsaeseo 1980 Nyeondae Yeoseongmisului Wichi” [The Position of ‘Women’s Art’ in the History of Korean Contemporary Art], Journal of Korean Modern & Contemporary Art History, vol.26 (2013): 134.

14. Son Hee-gyoung, “1980 Nyeondae Hanguk Yeoseongmisul Un-dong: Peminijeum Misulloseoui Seonggwawa Hangye” [The Korean Women’s Art Movement in the 1980s: Accomplishments and Limitations as Feminist Art] (Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University Graduate School, 2000). Jung Pil-Joo, “Hanguk Yeoseongmisulgaui Yeoseongjuui Jeongcheseonge Gwanhan Yeon-gu” [A Study of the Feminist Identity of Korean Women Artists] (Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University Graduate School, 2005): Kim yeonjoo, ”Hangukyeondaemisulsaeseo,” 140. See footnote 21.

15. Cho Seon-Ryeong, “Hanguk Peminijeum Misurui Eojewa Oneul – 80 Nyeondae Yeoseongjuui Misulgwaui Yeongyeoljeomeul Jungsimeu-ro,” [The Past and Present of Korean Feminist Art – Focusing on the Link with Feminist Art in the 1980s], Moonhwagwahak, no.49 (2007): 180.

16. Beck Jee-sook, “99 Yeoseongmisulje ‘Patjwideurui Haengjin’eul Bokseupada” [Reflecting on Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade], Yeoseonggwa Sahwe, no. 11 (2000). Furthermore, the reviews of male critics who did not conceal the “bemusement” of Beck Jee-sook can be found in the following: Kim Wonbang, Sim Sang-Yong, Park Young taik (Moderator: An In-gi), “Roundtable: Peminijeum Misurui Hyeonjuso – Dasiboneun Gaenyeommisulgwa Minimeollijeum” [Roundtable: The Current Status of Feminist Art – A Reexamination of Concept Art and Minimalism], Art (Current name: Art in Culture), November, 1999.

17. Beck, Ibid., 259-260.

18. Kim, “Hanguk Hyeondaemisulsaeseo Peminijeum Yeongusa,” 75.

2. The prior studies that will be discussed later generally agree with this sentiment.

3. “Women’s art” remains a controversial term in the Korean art community with regards to defining the relationship between feminism and visual art. Patjis on Parade stated that it intended for “women’s art” to acquire a meaning beyond art by women, but it appeared to call attention to feminist art and describe its emergence as that of art “by women,”, without a concrete definition of “women’s art.”

4. Kim Hong-hee, Women and Art (Seoul: Noonbit, 2003)

5. Kim Hyeonjoo, “The History of Feminist Studies in Korean Contemporary Art History,” Art History Forum no. 50 (2020): 60.

6. I refer to the following: Yang Eunhee, “Curators as Cultural Mediators: the Gwangju Biennial in the Context of Globalization of Korean Art Since the 1990s,” Journal of History of Modern Art (2016): 40.

7. Kim Hong-hee, “Introduction, Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade,” Feminist Artist Network (99 Women's Art Festival Organizing Committee), Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade (Seoul: Hongdesign, 1999), 13.

8. Cho Hyeok, “History of Korean Feminist Art, a Reconstruction of Discourses: The 1980s ‘Yeoseong misul (Women’s Art)’ and the 1990s ‘Postmodern Feminist Art,” Art History Forum, no.51 (2020); Park Sohyun, “Kim Honghee's Feminist/Postmodern Art History and the Historical Status of Lee Bul,” Journal of Korean Modern & Contemporary Art History no. 40 (2020).

9. Cho Hyeok (2020), op.cit., 99.

10. Cho Hyeok(2020), op.cit., 103-5.

11. Park Sohyun (2020), op.cit., 417.

12. I refer to the recent compilation titled Love and Ambition. In the discussion moderated by Lee Jinshil, with participants such as Kim Hyeonjoo and Yang Hyo-sil, Kim Hong-hee likewise questions the term yeoseong misul (women’s art), which describes the activities of artists in the 1980s. To this, the participants agreed with her concerns about the English translation of yeoseong misul, women’s art, which might cause the term to become misunderstood as simply “yeoryu(lady)” or fundamentalist feminist activism. At the same time, they suggest accepting yeoseong misul (women’s art) as historical fact and treating the term as a proper noun: Lee Jinshil, “Chaiwa Banbogui Sigandeul: Hanguk Peminijeum Misurui Eojewa Oneul” [Times of Difference and Repetitions: The Past and Present of Korean Feminist Art], Love and Ambition-The Time Difference of Contemporary Feminist Art (Seoul: Mediabus, 2021), 12-49.

13. Kim Hyeonjoo, “Hangukyeondaemisulsaeseo 1980 Nyeondae Yeoseongmisului Wichi” [The Position of ‘Women’s Art’ in the History of Korean Contemporary Art], Journal of Korean Modern & Contemporary Art History, vol.26 (2013): 134.

14. Son Hee-gyoung, “1980 Nyeondae Hanguk Yeoseongmisul Un-dong: Peminijeum Misulloseoui Seonggwawa Hangye” [The Korean Women’s Art Movement in the 1980s: Accomplishments and Limitations as Feminist Art] (Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University Graduate School, 2000). Jung Pil-Joo, “Hanguk Yeoseongmisulgaui Yeoseongjuui Jeongcheseonge Gwanhan Yeon-gu” [A Study of the Feminist Identity of Korean Women Artists] (Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University Graduate School, 2005): Kim yeonjoo, ”Hangukyeondaemisulsaeseo,” 140. See footnote 21.

15. Cho Seon-Ryeong, “Hanguk Peminijeum Misurui Eojewa Oneul – 80 Nyeondae Yeoseongjuui Misulgwaui Yeongyeoljeomeul Jungsimeu-ro,” [The Past and Present of Korean Feminist Art – Focusing on the Link with Feminist Art in the 1980s], Moonhwagwahak, no.49 (2007): 180.

16. Beck Jee-sook, “99 Yeoseongmisulje ‘Patjwideurui Haengjin’eul Bokseupada” [Reflecting on Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade], Yeoseonggwa Sahwe, no. 11 (2000). Furthermore, the reviews of male critics who did not conceal the “bemusement” of Beck Jee-sook can be found in the following: Kim Wonbang, Sim Sang-Yong, Park Young taik (Moderator: An In-gi), “Roundtable: Peminijeum Misurui Hyeonjuso – Dasiboneun Gaenyeommisulgwa Minimeollijeum” [Roundtable: The Current Status of Feminist Art – A Reexamination of Concept Art and Minimalism], Art (Current name: Art in Culture), November, 1999.

17. Beck, Ibid., 259-260.

18. Kim, “Hanguk Hyeondaemisulsaeseo Peminijeum Yeongusa,” 75.

Hur Hojeong

The Curator’s Dilemma

Feminism, curating, and writing history : (1) The Curator’s Dilemma

A speck of dust on a very smooth surface. A crack hidden in an uneven surface. Of the two, which is more difficult to find? Regardless of the answer, the act of writing history requires the painstaking process of discovering the specks of dust and hidden cracks within the established discourses— accounting for the smooth and the uneven surfaces. As a process that always takes place after the fact while at the same time taking place in the present, the act of writing history also primes the particles of dust and cracks within the self. The act of writing (the history of) contemporary Korean feminism likewise takes place in the same context.

The reboot in the term “feminist reboot” refers to this circumstance, a circumstance that cannot be understood in the absence of a continuity with the past but at the same time has entered a completely new phase. That is to say contemporary feminism encompasses different time periods. Likewise, within contemporary artwork there exists a sense of familiarity in the accumulated dirt and layered context of the past eras, which coexists with a sense of novelty. The exposure to and the attempt to understand the two time periods that are evident within the artwork and the social phenomenon naturally brings the curator face to face with the issue of writing history.

In the three-part series that will follow, I intend to maintain a focus on the point of intersection between “curating,” “feminism,” and “writing history.” In the first article, I examine the historic circumstances surrounding the 1990s (to the early 2000s), which are considered to be the beginning of Korean “contemporary” art.1 To this end, I briefly summarize prior research that attempts to describe feminism within the context of Korean contemporary art history. It is in this context that I define the relationship between visual art and feminism and also examine the curator’s dilemma that emerges in response.

* * *

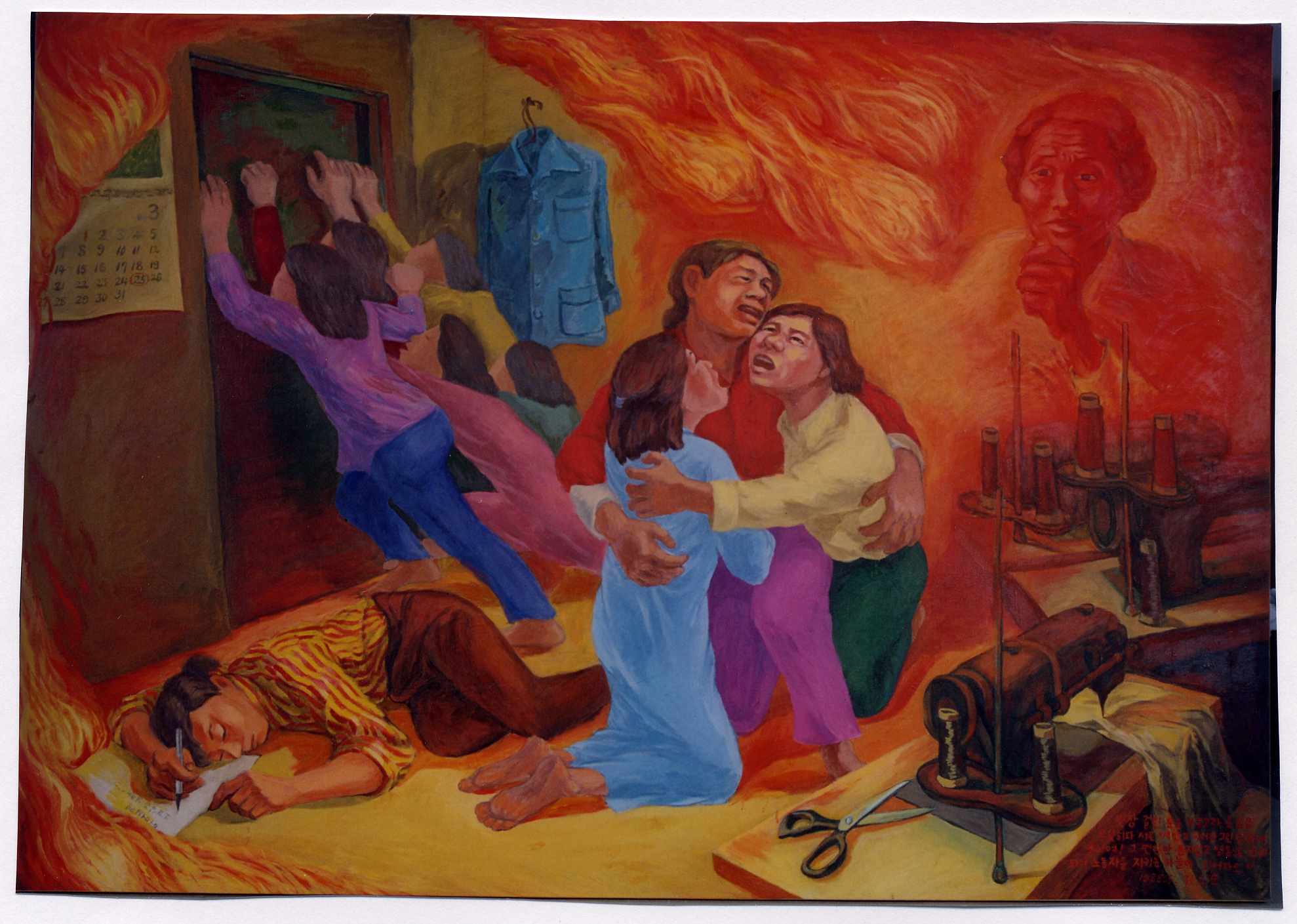

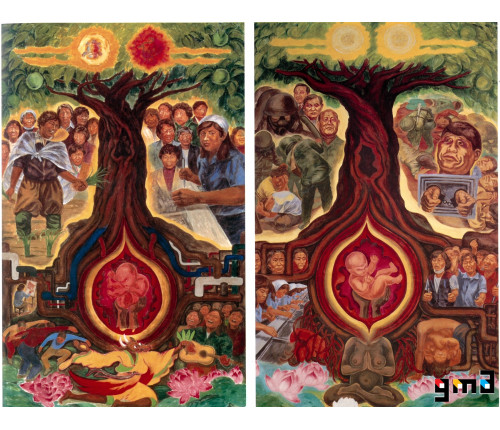

Descriptions of the currents of “feminism” in Korean contemporary art begin with “women’s art”, which caused a fracture within the Minjung art movement with its emergence in the 1980s.2 At the time, the primary actors of the women’s art movement felt that an awakening was necessary within mainstream Minjung art, which neglected the realities of women. They established the women's division and attempted to branch off and work independently. Notable women’s art exhibitions include the October Gathering’s [Siwol Moim] From Half to Whole (1985), Alternative Culture’s Let’s Burst Out (1988), and the Women’s Art Research Society's (Yeoseong misul yeonguhoe) annual exhibition Women and Reality (1988-1994). The proper critique and historicization of “women’s art” in the 1980s emerged for the first time in the 1990s, and Kim’s exhibitions take place in this context.

Kim Hong-hee’s curation of exhibitions and historical research and writing is referenced continuously, and subjected to numerous academic investigations and critiques. Her works are recognized as groundbreaking in many ways, and they have had a considerable effect on both the artworks of her contemporaries as well as of future generations. Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade, of which she was the chief organizer, is considered to be the exhibition that charted a genealogy of Korean “women’s art” that leads from the modern era to the 1990s3 Of all of the “Korean books that provide an overview of Korean contemporary art history from a feminist perspective,” Kim Hyeonjoo described Yeoseonggwa Misul,4 written by Kim Hong-hee, as the “only book that covers the broad spectrum of Western art history as well as Korean modern history and contemporary history from the 1980s to the 1990s.”5

As the first generation of Korean curators, Kim’s position has arguably crystallized as a result of a single trend that swept the art community during the 1990s to the early 2000s. According to Yang Eunhee, the popularization of international biennials led to the formal adoption of the term “curator” in Korea. This is when curation came to be recognized as an independent profession. Later, during the Korean reflection on charismatic curators, as exemplified by Harald Szeemann (1933-2005), the first generation of “independent” curators emerged during the 2000s.6 Kim Hong-hee is often mentioned in that context.

Within this context, Kim Hong-hee’s curatorial practice can be summed up as large-scale exhibitions that draw a topographical map of feminism in contemporary Korean art. In the preface to the introduction of Patjis, Kim wrote that the exhibition can be “largely divided into a retrospective of the artworks from the 1960s to the 1980s and a themed exhibition of contemporary artists in the 1990s, the intent of which was to examine the past and the present of Korean contemporary women’s art.”7 This was the primary goal of the exhibition. This is quite problematic, because the exhibition regarded the 1990s as a historic turning point and relegated the 1980s to the previous era, as part of an amorphous “past.” This premise of a “dramatic division” between the 1980s and the 1990s in Korean “women’s art” had not been questioned for some time following the Patjis exhibition.

However, recent studies have questioned this premise. Publishing an article in the same year, researchers Cho Hyeok and Park Sohyun view the specific formula of describing Korean feminist art history as originating from Kim Hong-hee. They examine Kim’s writings relating to Patjis and its precedent, Woman, The Difference and The Power (1994), and criticize the vague descriptions of “feminine” art, “feminist” art, and “femininity” and the fact that Kim historicizes the division between the 1980s and the 1990s. Cho believes that in taking on the mantle of the “era of women artists,”, the curator attempted to institutionalize feminism in haste before it had a chance to mature. Park views Kim as having adopted, without question, a male-centric mode of categorizing art history, applying a linear and occidental view of history, leading from modernism to postmodernism to Korean art. What is repeatedly made obvious is that the practice of writing history that emerged from Kim’s projects labeled Korean feminist art in the 1980s was incomplete or flawed.8

Cho Hyeok (2020) argues that it is necessary to “avoid the adoption of a teleological view of history that separates feminist art in the 1980s and the 1990s and regards [art in the 1990s] as having advanced beyond [art in the 1980s].”9 She argues that the temporal context of the 1990s is characterized by the popularization of postmodernist discourse, new art history, and cultural studies, and that critics and researchers of that time adopted a generational viewpoint and therefore created a division between 1990s art and both 1980s Minjung art as well as 1980s feminist art, which remained within the orbit of Minjung art.

She examined several prior studies and reflected on the reasons why feminist art in the 1980s was rejected in comparison to feminist art in the 1990s. First, such a disregard often falls in line with critiques of Minjung art, that 1980s art failed to discover any new stylistic forms and thus revealed its aesthetic limitations. In the same vein, “women’s art” in the 1980s became so preoccupied with ideology and class consciousness that it failed to manifest a “universal” model of womanhood. To this, Cho asks whether feminist art that prioritized class liberation should not be called feminist art, and she questions what precisely the nature of this “universal” model of womanhood and female aesthetics is.10

Park Sohyun (2020) offers a similar perspective. She argues that the division between the 1980s and the 1990s, which was an accepted premise in describing Korean feminist art, is the result of blind adherence to the general trends of critical and academic discourse that define Korean contemporary art history, which makes it difficult to find a place for feminist art within the grand narrative of Korean contemporary art history. It is also because “there is a lack of feminist reinterpretation and meta criticism” of formulaic descriptions of art history.”11

In short, given the importance and influence of Kim Hong-hee’s curatorial projects, a reflective examination of these projects is also required. And the historical task of examining feminism in contemporary Korean art returns once again to the 1980s. Reflecting on the undervaluation of feminist art in the 1980s, a view that has practically become canonized, Kim Hyeonjoo (2013) and Cho Seon-Ryeong (2007) have examined the notion of “women’s art.”12 Kim adopts “women’s art” as a term that describes a series of artistic activities that is observed in a particular time period. She writes that women's art is “both Minjung art as well as feminist art. It belongs at the intersection between the two.”13 She focuses on two master’s theses published in the 2000s, and borrowing from their arguments, suggests that “women’s art” has neither been recognized as an independent women’s aesthetic nor as Minjung art. Resistance towards activist art endeavors including Minjung art, have led to the rejection of women's art by the mainstream art community.14

Cho uses the term “women's art” in a similar context. Taking it one step further, she argues that “women's art” is the true feminist art form of Korea, distinct from Western feminist art. She argues that “In Korea, feminism from the very beginning emerged in the context of class and materialism.”15 She attempts to shed light on the fact that feminist art, with a sense of class and politics, saw its continuation in the work of women artists in the 1990s and the 2000s, following the emergence of postmodernist discourse.

However, in Kim Hong-hee's view of history, which she has adhered to even in recent times, “women’s art” in the 1980s continues to be qualitatively distinguished from “feminist art” since the 1990s, and furthermore, “postmodern feminist art” that emerged from the mid- to late 1990s to the early 2000s. However, as repeatedly confirmed in previous studies, what Kim Hong-hee defines as feminist is unclear. Moreover, feminist art, within this trajectory of presumed linear development, converges with the trend of new media/formal experiments found in postmodern/new generation art in general. When she assesses that she has established “women's aesthetics,” through her exhibitions and writings, and mentions major feminist artists and artworks, they too are categorized without a specific answer to the question of “what is women’s aesthetics,” and are selectively adopted as one of the so-called “postmodern arts,” highlighting the characteristic of its dispersion into separate elements.

Ultimately, for Kim Hong-hee, the 1980s is positioned as a huge void in the history of contemporary Korean art in preparation for the 1990s and the contemporary era. The identity of this void appears to give expression to some of the problems she must have faced as a first-generation curator.

: Was this the dilemma of a curator facing the contemporary call of globalization, burdened by an unresolved historical debt to Western modernism? Was the curator assigned with a kind of duty to identify the gap between the history and present of contemporary Korean art and to mend and bridge that gap? Was that a necessity introduced to secure the legitimacy and distinction of 1990s art, that is, new generation art and postmodern art? Was the leap to the “contemporary” through such a process not an art that would instantly suture two irreconcilable sides, such as the model and reality, or form and subject? If so, is the feminism of contemporary art, or the contemporaneity of feminist art achieved when the past is sacrificed to the void?

* * *

Lee Bul was one of the major upcoming, postmodernist, feminist artists championed by Kim. Beck Jee-sook, who participated in the planning of the theme exhibition of Patjis, published in the year following the exhibition an article titled “Review,” which examined the time surrounding the exhibition.16 In the article, she includes a chapter titled, “Why Lee Bul rejects the title of feminist artist.” She questions why Lee, who clearly appears to be a feminist artist, does not wish to receive attention as a feminist artist. She adds that this attitude was shared among young women artists (unlike artists in their 40s and 50s and were thus active in the 1980s) when the Women's Art Festival 99 was held.

[…] As an exhibition planner, when I select artists and their works, I am at times faced with a dilemma of two extremes. Do I choose the person with a greater sense of feminism, even though their work is lower in quality? Or do I choose the person without a clear sense of feminism, but who produces more cohesive work? If I were to take this question one step further, of course it becomes possible to ask another question. How is one to determine whether a person's sense of feminism is clearer or greater? Is it enough for the person to state as such, even if it does not appear clearly in the artwork? Or in contrast, how is one to determine the quality of the work? Is it correct to separate pure aesthetic value, deprived of all political subtext, into an independent criterion of evaluation?17

I was drawn, in particular, to the recursive sentences in the quote above. “In hindsight, I myself question whether I am truly a feminist.” “Do I choose the person with a greater sense of feminism, even though their work is lower in quality? Or do I choose the person without a clear sense of feminism, but who produces more cohesive work?” The questions Beck Jee-sook asked herself as a curator are surprisingly repeated in today’s so-called “feminist exhibitions” and their critiques. Of course, now it appears the question needs adjustment.

A speck of dust on a very smooth surface. A crack hidden in an uneven surface. Of the two, which is more difficult to find? Regardless of the answer, the act of writing history requires the painstaking process of discovering the specks of dust and hidden cracks within the established discourses— accounting for the smooth and the uneven surfaces. As a process that always takes place after the fact while at the same time taking place in the present, the act of writing history also primes the particles of dust and cracks within the self. The act of writing (the history of) contemporary Korean feminism likewise takes place in the same context.

The reboot in the term “feminist reboot” refers to this circumstance, a circumstance that cannot be understood in the absence of a continuity with the past but at the same time has entered a completely new phase. That is to say contemporary feminism encompasses different time periods. Likewise, within contemporary artwork there exists a sense of familiarity in the accumulated dirt and layered context of the past eras, which coexists with a sense of novelty. The exposure to and the attempt to understand the two time periods that are evident within the artwork and the social phenomenon naturally brings the curator face to face with the issue of writing history.

In the three-part series that will follow, I intend to maintain a focus on the point of intersection between “curating,” “feminism,” and “writing history.” In the first article, I examine the historic circumstances surrounding the 1990s (to the early 2000s), which are considered to be the beginning of Korean “contemporary” art.1 To this end, I briefly summarize prior research that attempts to describe feminism within the context of Korean contemporary art history. It is in this context that I define the relationship between visual art and feminism and also examine the curator’s dilemma that emerges in response.

* * *

Kim Hong-hee’s curation of exhibitions and historical research and writing is referenced continuously, and subjected to numerous academic investigations and critiques. Her works are recognized as groundbreaking in many ways, and they have had a considerable effect on both the artworks of her contemporaries as well as of future generations. Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade, of which she was the chief organizer, is considered to be the exhibition that charted a genealogy of Korean “women’s art” that leads from the modern era to the 1990s3 Of all of the “Korean books that provide an overview of Korean contemporary art history from a feminist perspective,” Kim Hyeonjoo described Yeoseonggwa Misul,4 written by Kim Hong-hee, as the “only book that covers the broad spectrum of Western art history as well as Korean modern history and contemporary history from the 1980s to the 1990s.”5

As the first generation of Korean curators, Kim’s position has arguably crystallized as a result of a single trend that swept the art community during the 1990s to the early 2000s. According to Yang Eunhee, the popularization of international biennials led to the formal adoption of the term “curator” in Korea. This is when curation came to be recognized as an independent profession. Later, during the Korean reflection on charismatic curators, as exemplified by Harald Szeemann (1933-2005), the first generation of “independent” curators emerged during the 2000s.6 Kim Hong-hee is often mentioned in that context.

Within this context, Kim Hong-hee’s curatorial practice can be summed up as large-scale exhibitions that draw a topographical map of feminism in contemporary Korean art. In the preface to the introduction of Patjis, Kim wrote that the exhibition can be “largely divided into a retrospective of the artworks from the 1960s to the 1980s and a themed exhibition of contemporary artists in the 1990s, the intent of which was to examine the past and the present of Korean contemporary women’s art.”7 This was the primary goal of the exhibition. This is quite problematic, because the exhibition regarded the 1990s as a historic turning point and relegated the 1980s to the previous era, as part of an amorphous “past.” This premise of a “dramatic division” between the 1980s and the 1990s in Korean “women’s art” had not been questioned for some time following the Patjis exhibition.

However, recent studies have questioned this premise. Publishing an article in the same year, researchers Cho Hyeok and Park Sohyun view the specific formula of describing Korean feminist art history as originating from Kim Hong-hee. They examine Kim’s writings relating to Patjis and its precedent, Woman, The Difference and The Power (1994), and criticize the vague descriptions of “feminine” art, “feminist” art, and “femininity” and the fact that Kim historicizes the division between the 1980s and the 1990s. Cho believes that in taking on the mantle of the “era of women artists,”, the curator attempted to institutionalize feminism in haste before it had a chance to mature. Park views Kim as having adopted, without question, a male-centric mode of categorizing art history, applying a linear and occidental view of history, leading from modernism to postmodernism to Korean art. What is repeatedly made obvious is that the practice of writing history that emerged from Kim’s projects labeled Korean feminist art in the 1980s was incomplete or flawed.8

Cho Hyeok (2020) argues that it is necessary to “avoid the adoption of a teleological view of history that separates feminist art in the 1980s and the 1990s and regards [art in the 1990s] as having advanced beyond [art in the 1980s].”9 She argues that the temporal context of the 1990s is characterized by the popularization of postmodernist discourse, new art history, and cultural studies, and that critics and researchers of that time adopted a generational viewpoint and therefore created a division between 1990s art and both 1980s Minjung art as well as 1980s feminist art, which remained within the orbit of Minjung art.

She examined several prior studies and reflected on the reasons why feminist art in the 1980s was rejected in comparison to feminist art in the 1990s. First, such a disregard often falls in line with critiques of Minjung art, that 1980s art failed to discover any new stylistic forms and thus revealed its aesthetic limitations. In the same vein, “women’s art” in the 1980s became so preoccupied with ideology and class consciousness that it failed to manifest a “universal” model of womanhood. To this, Cho asks whether feminist art that prioritized class liberation should not be called feminist art, and she questions what precisely the nature of this “universal” model of womanhood and female aesthetics is.10

Park Sohyun (2020) offers a similar perspective. She argues that the division between the 1980s and the 1990s, which was an accepted premise in describing Korean feminist art, is the result of blind adherence to the general trends of critical and academic discourse that define Korean contemporary art history, which makes it difficult to find a place for feminist art within the grand narrative of Korean contemporary art history. It is also because “there is a lack of feminist reinterpretation and meta criticism” of formulaic descriptions of art history.”11

In short, given the importance and influence of Kim Hong-hee’s curatorial projects, a reflective examination of these projects is also required. And the historical task of examining feminism in contemporary Korean art returns once again to the 1980s. Reflecting on the undervaluation of feminist art in the 1980s, a view that has practically become canonized, Kim Hyeonjoo (2013) and Cho Seon-Ryeong (2007) have examined the notion of “women’s art.”12 Kim adopts “women’s art” as a term that describes a series of artistic activities that is observed in a particular time period. She writes that women's art is “both Minjung art as well as feminist art. It belongs at the intersection between the two.”13 She focuses on two master’s theses published in the 2000s, and borrowing from their arguments, suggests that “women’s art” has neither been recognized as an independent women’s aesthetic nor as Minjung art. Resistance towards activist art endeavors including Minjung art, have led to the rejection of women's art by the mainstream art community.14

Cho uses the term “women's art” in a similar context. Taking it one step further, she argues that “women's art” is the true feminist art form of Korea, distinct from Western feminist art. She argues that “In Korea, feminism from the very beginning emerged in the context of class and materialism.”15 She attempts to shed light on the fact that feminist art, with a sense of class and politics, saw its continuation in the work of women artists in the 1990s and the 2000s, following the emergence of postmodernist discourse.

However, in Kim Hong-hee's view of history, which she has adhered to even in recent times, “women’s art” in the 1980s continues to be qualitatively distinguished from “feminist art” since the 1990s, and furthermore, “postmodern feminist art” that emerged from the mid- to late 1990s to the early 2000s. However, as repeatedly confirmed in previous studies, what Kim Hong-hee defines as feminist is unclear. Moreover, feminist art, within this trajectory of presumed linear development, converges with the trend of new media/formal experiments found in postmodern/new generation art in general. When she assesses that she has established “women's aesthetics,” through her exhibitions and writings, and mentions major feminist artists and artworks, they too are categorized without a specific answer to the question of “what is women’s aesthetics,” and are selectively adopted as one of the so-called “postmodern arts,” highlighting the characteristic of its dispersion into separate elements.

Ultimately, for Kim Hong-hee, the 1980s is positioned as a huge void in the history of contemporary Korean art in preparation for the 1990s and the contemporary era. The identity of this void appears to give expression to some of the problems she must have faced as a first-generation curator.

: Was this the dilemma of a curator facing the contemporary call of globalization, burdened by an unresolved historical debt to Western modernism? Was the curator assigned with a kind of duty to identify the gap between the history and present of contemporary Korean art and to mend and bridge that gap? Was that a necessity introduced to secure the legitimacy and distinction of 1990s art, that is, new generation art and postmodern art? Was the leap to the “contemporary” through such a process not an art that would instantly suture two irreconcilable sides, such as the model and reality, or form and subject? If so, is the feminism of contemporary art, or the contemporaneity of feminist art achieved when the past is sacrificed to the void?

* * *

. . . In short, young artists would rather adopt feminism as a facet of their work, rather than boxing their works into feminist art. . . . In hindsight, I myself question whether I am truly a feminist. At times I think I am, but at times I think not. For example, I undergo a crisis of identity when it feels that feminism, rather than expanding the horizon of culture, appears to limit it. In this case, which is wrong? Is it the limited definition of feminism? Or is it the narrowness of my perception, which fails to interpret surrounding phenomena and social mechanisms through the lens of feminism?

[…] As an exhibition planner, when I select artists and their works, I am at times faced with a dilemma of two extremes. Do I choose the person with a greater sense of feminism, even though their work is lower in quality? Or do I choose the person without a clear sense of feminism, but who produces more cohesive work? If I were to take this question one step further, of course it becomes possible to ask another question. How is one to determine whether a person's sense of feminism is clearer or greater? Is it enough for the person to state as such, even if it does not appear clearly in the artwork? Or in contrast, how is one to determine the quality of the work? Is it correct to separate pure aesthetic value, deprived of all political subtext, into an independent criterion of evaluation?17

I was drawn, in particular, to the recursive sentences in the quote above. “In hindsight, I myself question whether I am truly a feminist.” “Do I choose the person with a greater sense of feminism, even though their work is lower in quality? Or do I choose the person without a clear sense of feminism, but who produces more cohesive work?” The questions Beck Jee-sook asked herself as a curator are surprisingly repeated in today’s so-called “feminist exhibitions” and their critiques. Of course, now it appears the question needs adjustment.

: Is “feminist consciousness” an optional stance that can be taken up or abandoned? Isn't the feminist self-consciousness of the artist/curator being understood as a feminist attitude toward art practice? Does the lack of a feminist self-consciousness lead to the inability to practice feminist art? Conversely, do artists/curators who call themselves feminists produce art with a feminist attitude? Is it the curator’s fateful task to quibble over the level, form, and consciousness of a work?

In summarizing the achievements of feminist studies in Korean art history for the past thirty years, Kim Hyeonjoo adopts a clear stance on “feminist art history.” “Feminist art history” does not exist as a separate entity. Rather, feminism seeks to criticize the shortcomings of existing art history and establish an alternate art history. She emphasizes that it is necessary to discard the term “feminist art history” and to use the “feminist critique of art history” and “feminist intervention in art history” instead.18 If that is the case, how should curators, as participants in the writing of history, overcome the personal dilemma that arises as a result of their occupying the intersection of feminism and visual art? It is likely impossible to answer this question by searching for “feminist artists” and “feminist art,” and furthermore “feminist art history.” How then are we as curators and art historians to conceive and practice feminist critiques of, and intervention in, contemporary art?

- Share

Copy URL

Copy URL

Women's Art Festival 99: Patjis on Parade, Exhibition brochure, Image provided by MMCA Art Research Center.

Kim Insoon, Twenty-Two Daughters Died in Green Hill Fire, 1988, Acrylic on canvas, 150×190cm. Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) collection.

Kim Insoon, We Women are the Ones Producing Life 1 & 2, 1995, Acrylic on canvas, 400x250cm. Gwangju Museum of Art.

Lee Bul, Sorry for Suffering—You Think I’m a Puppy on a Picnic?, 1990, Performance, 12 days, The 2nd Japan and Korea Performance Festival, Gimpo Airport, Korea; Narita Airport, Meiji Shrine, Harajuku, Otemachi Station, Koganji Temple, Asakusa, Shibuya, University of Tokyo and Tokiwaza Theater, Tokyo, Japan. Courtesy of the artist.

Lee Bul, Cyborg W5, 1999, Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 150×55×90cm. MMCA.