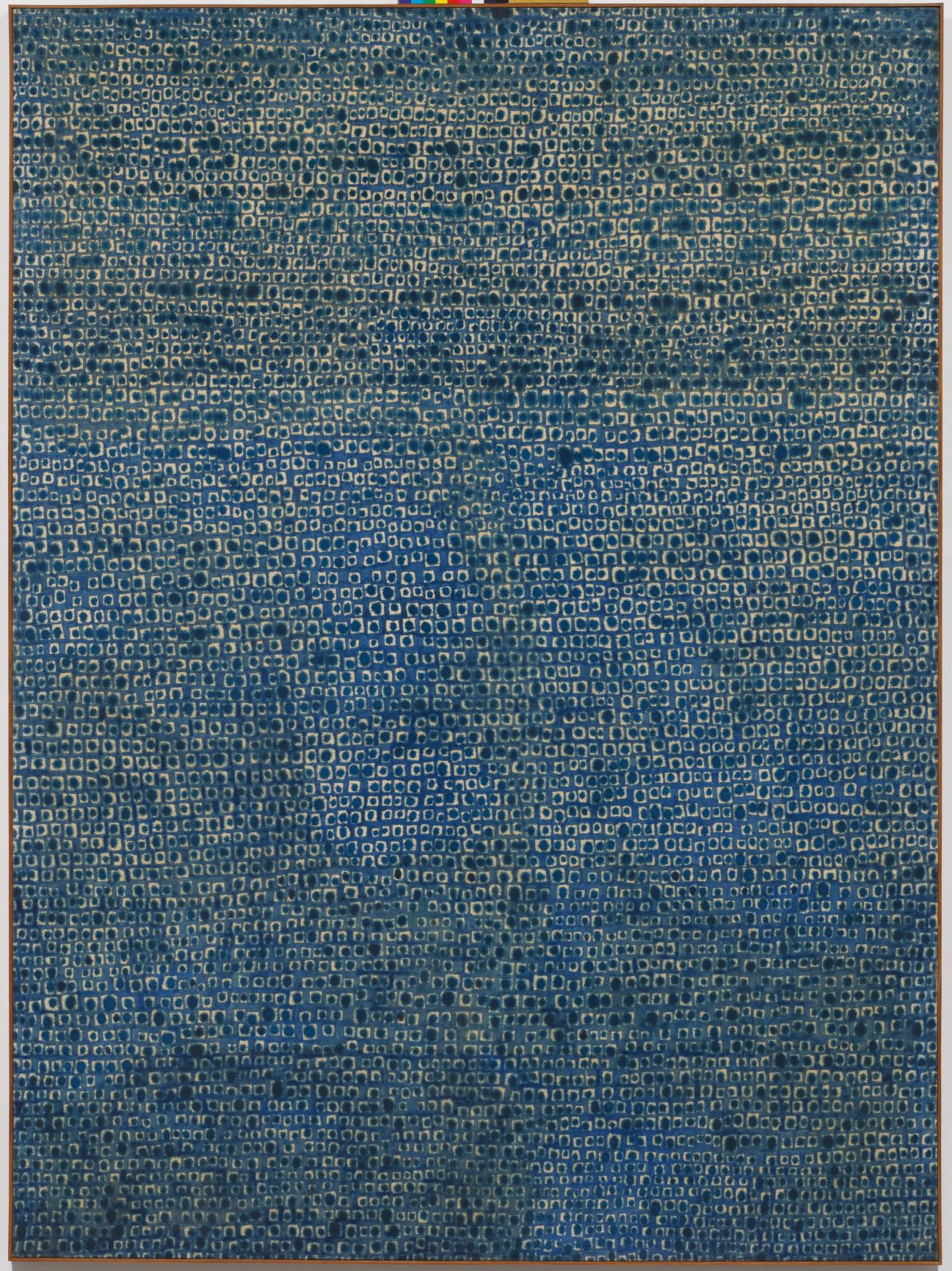

Park Seo-Bo, Ecriture No.16-78-81, 1981, Oil paint and graphite on cotton, 130×162cm. MMCA collection

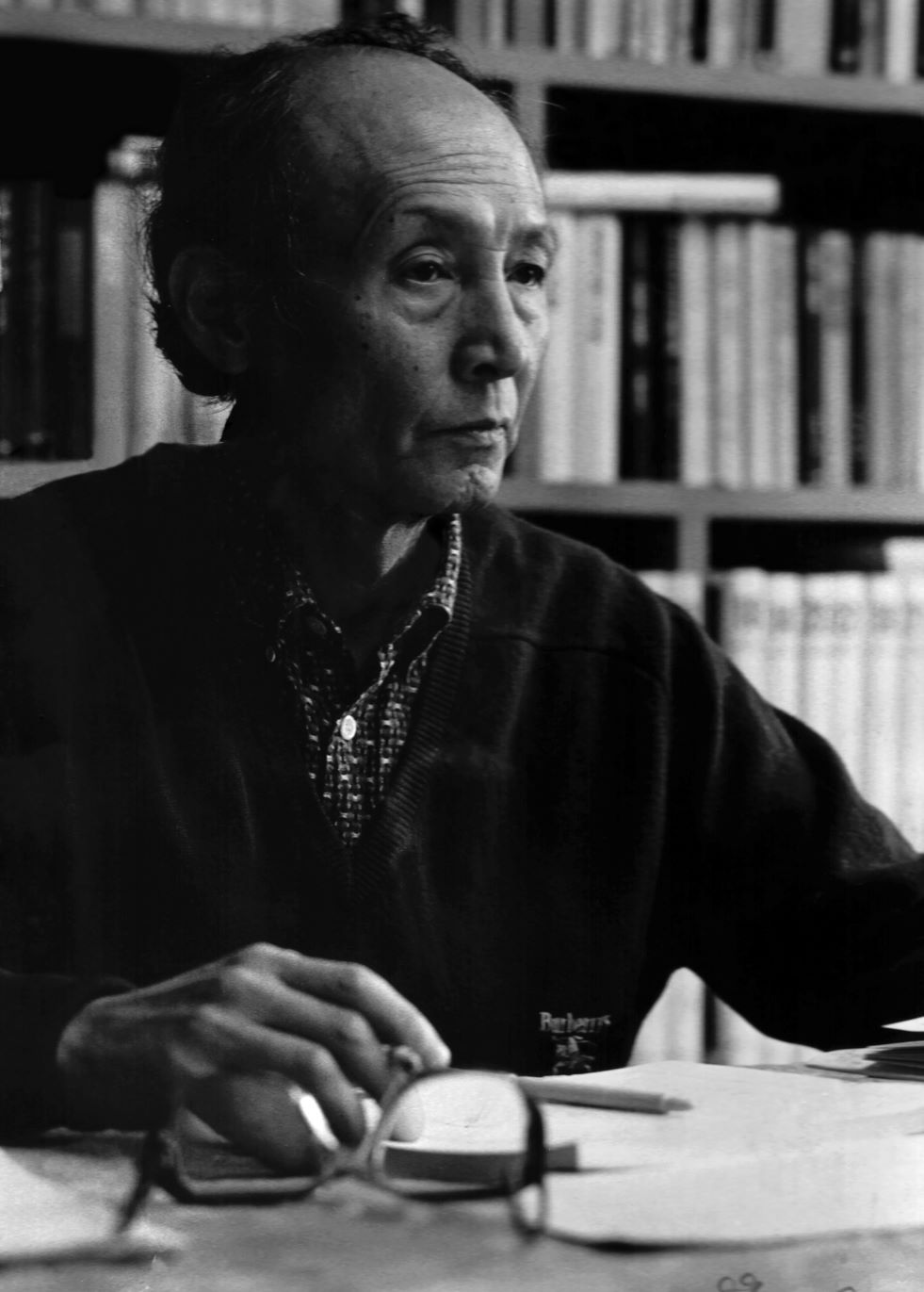

Park Seo-Bo

* Source: MMCA

Related

-

Ecole de Séoul

The Ecole de Seoul is an art group founded by Park Seo-Bo and others in 1975. Their first exhibition was held at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Korea from July 30 to August 5, 1975. For the second exhibition in 1976, they adopted a new system, used for the first time in Korea, where an independent commissioner selected artists. Founding member Park Seo-Bo said, “While the Indépendants Exhibition and the Seoul Contemporary Art Festival aim to find new artists and expand the territory of contemporary art, the Ecole de Séoul is a miniature reflection of our contemporary art community.”

-

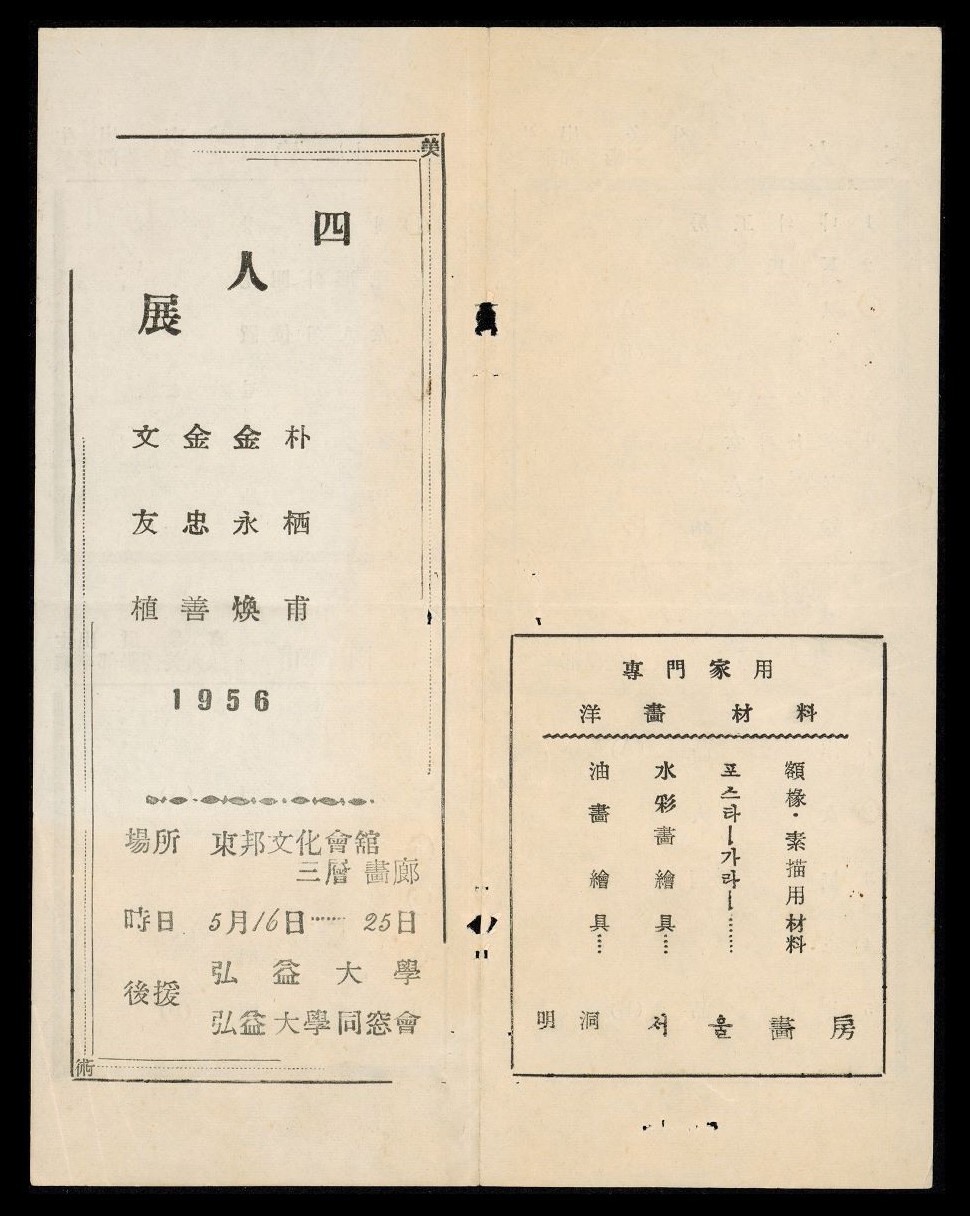

Four Artists Exhibition

An exhibition held at the Eastern Cultural Center from May 16 to May 25, 1956. The featured artists—Kim Younghwan, Kim Chungsun, Moon Woosik, and Park Seo-Bo—were alumni of Hongik University. Together protesting in front of the show itself, they declared their opposition to the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon). The Korean art community of the day, which centered around the National Art Exhibition, imitated the manner of Japanese Academicism, and their declaration was the result of these younger artists’ resistance to this practice. They opposed the realist focus espoused within the National Art Exhibition and influenced the founding of the Modern Art Association, the Hyundae Fine Artists Association, the Creative Art Association [Changjak misul hyeopoe], Sinjohyeongpa, and the Paek Yang Painting Association.

-

Independants (1972)

Indépendants is an exhibition held by Korean Fine Arts Association [Hanguk misul hyeophoe] to solve problems of selecting artworks for international exhibitions. The first Independants exhibition was a contest held in the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea at Gyeongbokgung Palace from August 1 through 15 in 1972 to nominate candidates to participate in the eighth Paris Biennale and the fifth Spain Biennale. Following the principle of “no evaluation, no award” advocated by the Salon des Indépendants, which began in France in 1884, all works submitted to Indépendants were exhibited without any evaluation. Initially, the participants were limited to young artists under the age of thirty-five, with no restrictions on the content of their works. Thus, Indépendants was viewed as providing opportunities for unknown, rising artists to join international exhibitions regardless of their educational background and work experience and it inspired them to create. However, as the scope of international exhibitions expanded and the age limit of thirty-five was removed, it eventually came to “be dominated by artists of the extreme abstract art movement.” Its last exhibition was the eighth edition held in July 1980 when Park Seo-Bo, who played a leading role in organizing the Independants exhibitions, lost the election for the chairman of the Korean Fine Arts Association.

Find More

-

Department of Art at Hongik University

Established in 1949, the Department of Art at Hongik University consists of one art theory department and eleven practice-based departments, including painting, Oriental painting, printmaking, sculpture, woodworking and furniture design, metal art and design, ceramics and glass, textile art and fashion design, visual communication design, and industrial design. In 1955, it moved from Jongro-gu, Seoul to the current location in Sangsu-dong, Mapo-gu, Seoul. The history of the College of Fine Arts can be largely divided into the period of the Department of Fine Arts from 1949 through 1953, the period of the School of Fine Arts from 1954 through 1971, and the period of the College of Fine Arts from 1972 until now. In March 1953, the Department of Fine Arts produced the first six graduates, and in the following year the School of Fine Arts with three departments was established. In December 1971, it was upgraded to a college, which exists up to the present. Several exhibitions organized by its graduates are notable, including the Four Artists Exhibition held in 1956 as the first anti-National Art Exhibition (Daehanminguk misul jeollamhoe or Gukjeon) by the third and fourth classes of graduates and the Union Exhibition of Korean Young Artists held in 1967 by graduates from the 1960s as an effort to realize experimental art.

-

Lee Yil

Lee Yil(1932-1997) was a first-generation critic whose art criticism was based on art theories and greatly impacted the formation of Korean modernism. He was born in Gangseo, Pyeongannam-do Province and his real name is Lee Jinsik. While attending Pyongyang High School, Lee defected to South Korea and went to Gyeongbok High School in Seoul. After graduation, he entered the French Literature Department at Seoul National University but dropped out and moved to Paris. In 1961, he studied archaeology and art history at Sorbonne University. There, he worked as a Paris correspondent for the Chosun Ilbo newspaper. In 1964, he translated and published L’aventure de l’art abstrait (The Adventure of Abstract Art) by Michel Ragon. Returning to Korea in 1965, Lee began practicing art criticism in earnest. In 1966, he joined Hongik University as a professor of art theory, and he held the position for thirty years until his retirement in 1997. He wrote A Trajectory of Contemporary Art that introduced contemporary art of the West in 1974. Among his translated works are Naissance d’un Art Nouveau (Birth of Art Nouveau) (1974) by Michel Ragon, The History of World Painting (1974), and History of Art by H.W. Janson (1984). From the 1980s, he published books on art criticism, including Korean Art: The Face of Today (1982) and Reduction and Expansion of Contemporary Art (1991). After his death, the collections of his posthumous manuscripts, Lee Yil: Art Criticism Journal (1998) and The Critic Lee Yil Anthology in two volumes (2013), were published. Lee Yil’s art criticism activities can be divided largely into two periods. The former period spans from the time he returned from France to the early 1970s. During this period, Lee was interested in anti-art such as Dadaism and Nouveau Réalisme (New Realism). He inspired the formation of the Union Exhibition of Korean Young Artists that was brought together in solidarity by the generation who experienced the April 19 Revolution. Serving as a founding member and theorist of the Korean Avant Garde Association (referred to as AG) established in 1969, he developed criticism that laid the foundation for the formation of avant-garde art that emphasized experimentation. Around 1971 and 1972, he redirected his attention to art reflecting Korean culture and the spirit of Koreans rather than avant-garde focused on resistance. In the latter period, he stressed a “return to the primordial.” With his distinctive critical concepts, such as “reduction and expansion” and “pan-naturalism,” he actively supported the Korean Minimalism school of painters, especially Dansaekhwa artists. Lee’s critical perspective became a cornerstone in the narrative of Korean contemporary art history in the 1970s.

-

Abstract art

A term which can be used to describe any non-figurative painting or sculpture. Abstract art is also called non-representational art or non-objective art, and throughout the 20th century has constituted an important current in the development of Modernist art. In Korea, Abstract art was first introduced by Kim Whanki and Yoo Youngkuk, students in Japan who had participated in the Free Artists Association and the Avant-Garde Group Exhibition during the late 1930s. These artists, however, had little influence in Korea, and abstract art flourished only after the Korean War. In the 1950s so called “Cubist images,” which separated the object into numerous overlapping shapes, were often described as Abstractionist, but only with the emergence of Informel painting in the late 1950s could the term “abstract” be strictly used to describe the creation of works that did not reference any exterior subject matter. The abstract movements of geometric abstractionism and dansaekhwa dominated the art establishment in Korea in the late-1970s. By the 1980s, however, with the rising interest in the politically focused figurative art of Minjung, abstraction was often criticized as aestheticist, elitist, and Western-centric.