Image provided by Gallery Hyundai

Gallery Hyundai

* Source: Multilingual Glossary of Korean Art. Korea Arts Management Service

Related

-

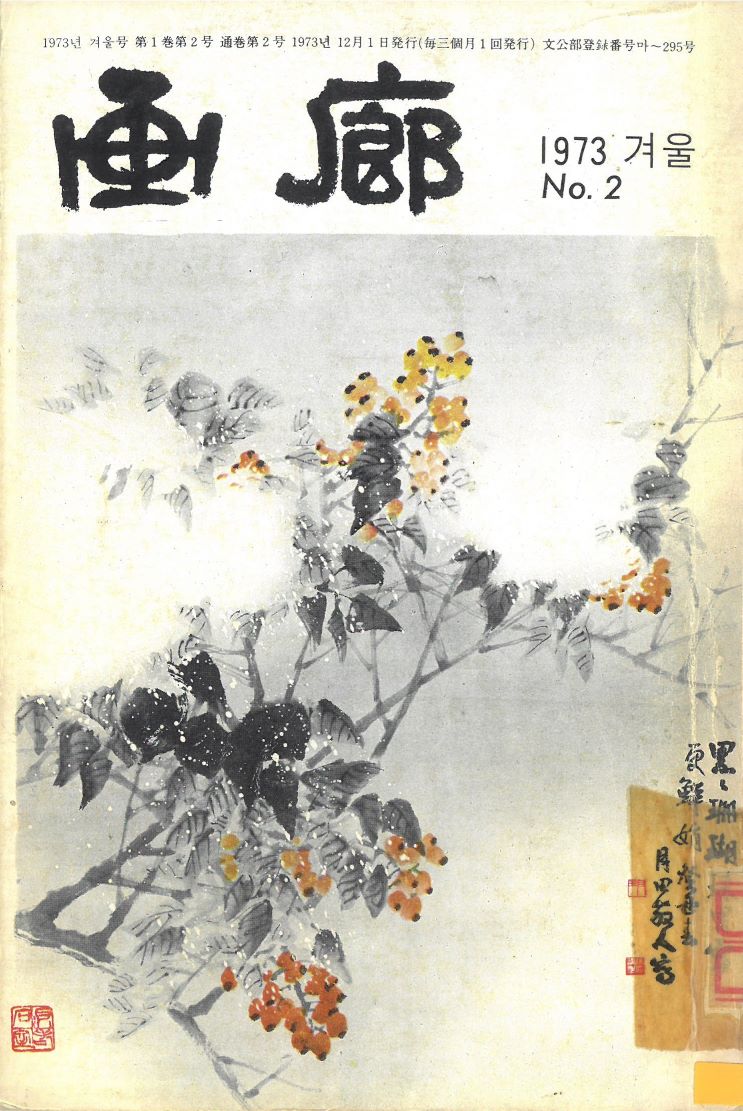

Hwarang

Hwarang was founded in September 1973 by Gallery Hyundai (a space former titled Hyundai Hwarang). The magazine’s motto was to provide a “young magazine created by young publishers, editors, and readers” and aimed to act as an intermediary between art and the public by discovering outstanding artists and their works. Art experts such as Oh Kwangsu, Park Raekyung, Lee Hongwoo, Lee Guyeol and Heo Younghwan participated as members of the editorial board. The magazine utilized a small size (19x13cm) for readers to hold and read it comfortably. The cover of the first issue was Cheon Kyung-ja’s A Portrait of a Lady, and each issue featured an interview with an artist, an atelier tour, a collector's essay, a review, and a discussion. It attempted to transform itself into Hyundaimisul (Modern Art) starting with the autumn issue of 1988 and continued until 1992. A total of 76 volumes (60 volumes of Hwarang and 16 volumes of Hyundaimisul) played a role in conveying knowledge to art dealers, buyers, and general art lovers, despite some criticism that they advertised artists excessively.

-

Abstract art

A term which can be used to describe any non-figurative painting or sculpture. Abstract art is also called non-representational art or non-objective art, and throughout the 20th century has constituted an important current in the development of Modernist art. In Korea, Abstract art was first introduced by Kim Whanki and Yoo Youngkuk, students in Japan who had participated in the Free Artists Association and the Avant-Garde Group Exhibition during the late 1930s. These artists, however, had little influence in Korea, and abstract art flourished only after the Korean War. In the 1950s so called “Cubist images,” which separated the object into numerous overlapping shapes, were often described as Abstractionist, but only with the emergence of Informel painting in the late 1950s could the term “abstract” be strictly used to describe the creation of works that did not reference any exterior subject matter. The abstract movements of geometric abstractionism and dansaekhwa dominated the art establishment in Korea in the late-1970s. By the 1980s, however, with the rising interest in the politically focused figurative art of Minjung, abstraction was often criticized as aestheticist, elitist, and Western-centric.

-

Lee Gu-yeol

Lee Gu-yeol(1932-2020) was the first art journalist, an art critic, and a researcher of modern art in Korea. Born in Yeonbaek, Hwanghae-do Province, Lee went to South Korea during the Korean War. He enlisted in the army as a cadet, completed infantry and artillery schools, and served as an officer during the war. After being discharged as a captain in 1958, he joined World Telecommunications and worked in the publications department. In 1959, he enrolled as a junior in the College of Fine Arts at Hongik University, but he could not finish his studies. He worked as an art reporter in the culture desk of Segye Ilbo newspaper (renamed the Minguk Ilbo in 1960) and then as a reporter and deputy head of the culture desk of Kyunghyang Shinmun newspaper in and after 1962. In 1970, he transferred to Seoul Sinmun newspaper and served as the head of its culture desk. He became the head of the culture desk of Daehan Ilbo newspaper in 1972 but ended his journalistic career when the company ceased to publish in 1975. In 1964, Lee was in charge of editing the quarterly magazine Misul (Art) (published by Munhwa Gyoyuk Chulpansa). He also organized the publication of fifteen volumes of the Complete Collection of Korean Art (sponsored by Donghwa Chulpan Gongsa) and worked as chief editor from 1973 through 1975. He served as president of the Korean Art Critics Association (1984–1985), a member of the Cultural Heritage Committee of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (1992–1999), and as director of exhibition projects at the Seoul Arts Center (1993–1996). He also opened the Korean Modern Art Research Institute and published its irregular periodical Modern Art of Korea from the first to fifth issues (1975–1977). His books include The Realm of Painting: The Life and Art of Idang (1968), A Study on Modern Korean Art (1972), The Development of Modern Korean Art (1982), Research on Modern Korean Art History (1992), History of Modern Korean Painting (1993), 50 Years of North Korean Art (2001), The Story behind Modern Korean Art (2005), Rha Hyeseok: The Woman Who Drew Her Fiery Life (2011), Korean Cultural Heritage: A History of Suffering (2013), and My Days as an Art Reporter (2014). In 2018, he published two volumes of his self-edited literary collection Miscellany by Cheongyeo to celebrate his turning eighty-eight. Lee Gyu-yeol played a crucial role in the establishment of the Archives of Korean Art Journal, the first art archives in Korea, in December 1998 by donating his materials related to modern and contemporary art to the Samsung Museum of Art. In 2015, he donated more than 4,000 items to Gacheon Museum of the Gil Cultural Foundation. He passed away in 2020 at the age of eighty-nine.

Find More

-

Park Sookeun

Park Sookeun (1914-1965) graduated from Yanggu Elementary School and was a self-taught artist. In 1932, he began his career when he was selected for the 11th Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe], an event which he would subsequently be chosen for eight times. He founded Juhohoe (1940-1944) in Pyongyang with Choi Youngrim and Chang Reesouk. His work earned a special award for the second National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) in 1953 and he became a Noteworthy Artist at the National Art Exhibition in 1959 and a judge in 1962. Park Sookeun’s works in the 1940s portrayed the humble lives of Koreans or somewhat resigned scenes of everyday life. After the Korean War, he often used thick gray lines to draw such work, often featuring subjects such trees, girls, and women. His work utilized various techniques, such as the elimination of shadow, emphasized outlines, or thickly daubed colors applied with a granite-like finish. In the 1960s, his unique expressive technique developed further, and enabled him to subtly capture Korean sensibilities through scenes of the everyday lives of girls and mothers in Korea. Park Sookeun excelled in describing the lives and sensibilities of ordinary Koreans.

-

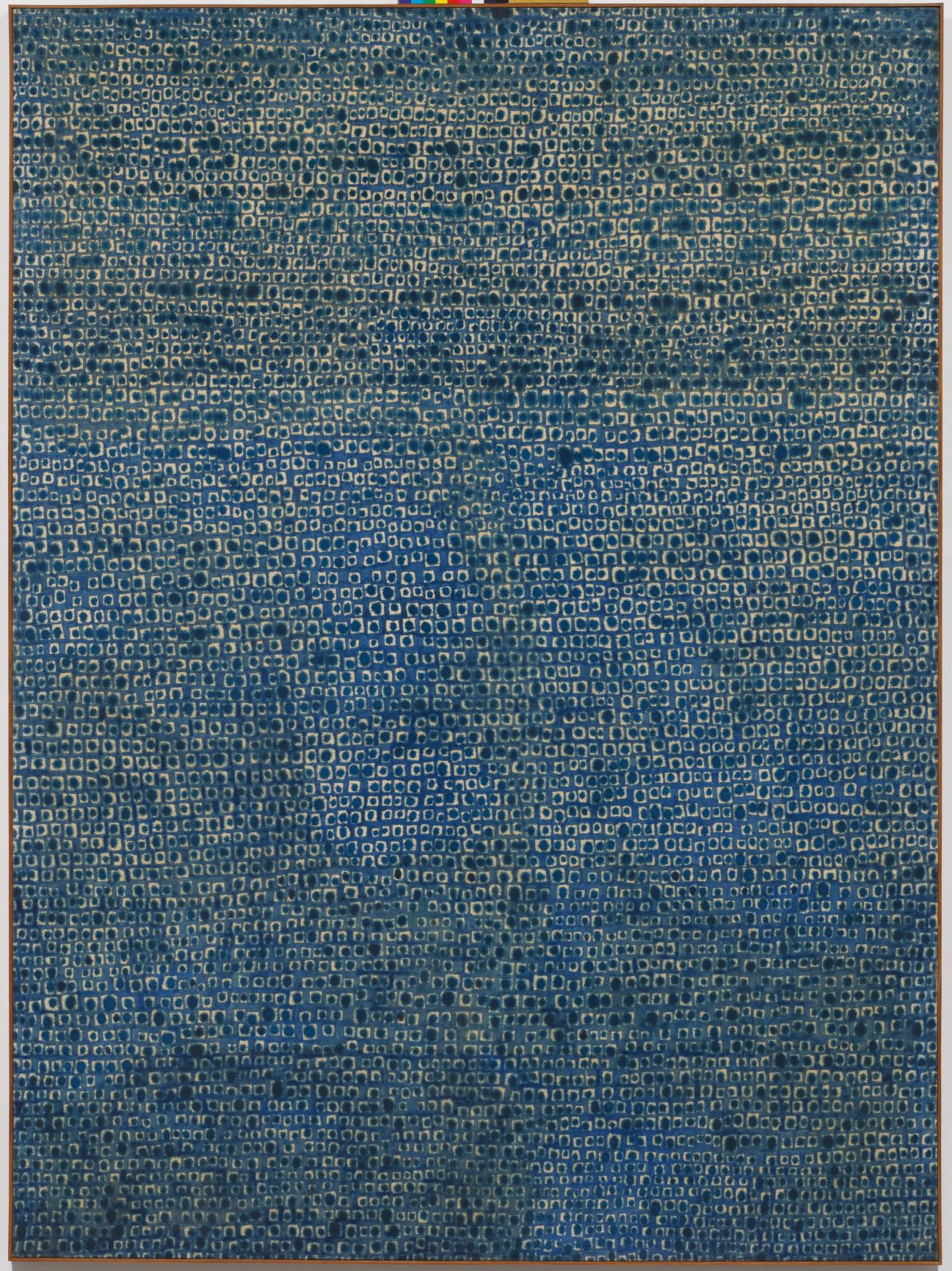

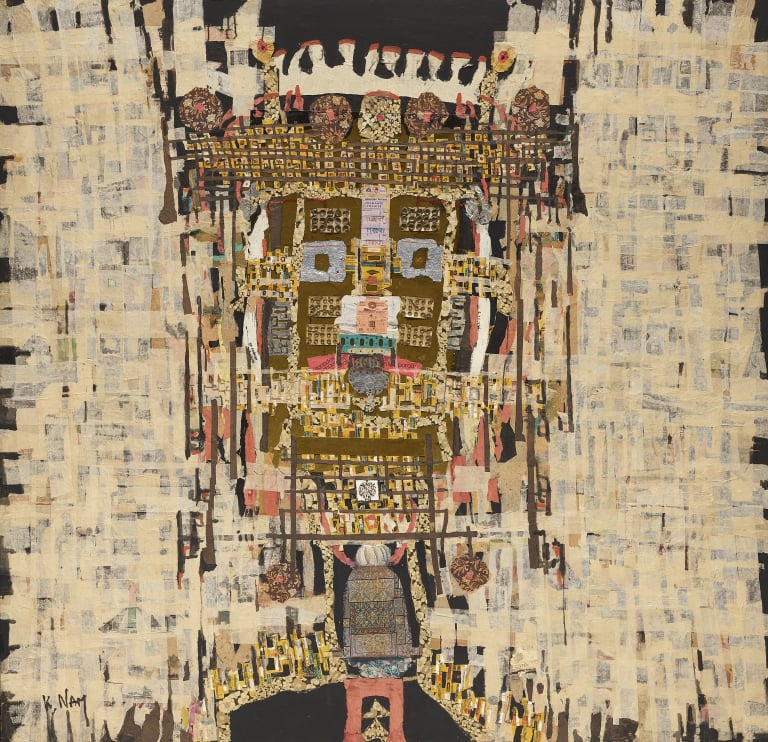

Nam Kwan

Nam Kwan (1911-1990) graduated from the Taiheiyo Art School in 1935 and performed research for two further years. He submitted his work to the Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition (Munbuseong misul jeollamhoe), Donggwang Group Exhibition, and the Gukhwa Group Exhibition in Tokyo. In 1954, he attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumièrec in Paris and was invited to submit his work to the Avant-Garde Art Exhibition Salon de Mai and Fleuve Art Gallery. After returning to Korea in 1968, he became a professor at Hongik University. Before he went to Paris, he created portrait and landscape paintings, emphasizing lyrical colors and free expression. While Nam Kwan’s early works tended to focus on figuration, he switched to Oriental style of abstraction, influenced by Parisian Art Informel. In 1962, he experimented with abstract works symbolizing ancient letter inscriptions and after his return to Korea in 1968 he developed a style based on mask abstraction. He liked to utilize abstract letters, lines, and figures using blue as an organising palette. Nam Kwan became a leading figure in the abstract art movement in Korea after independence, and he is particularly well-known for reconfiguring ancient inscriptions as abstract idioms within his work.

-

To Sangbong

To Sangbong (1902-1977, pen name Docheon) learned western painting from Ko Huidong at Bosung High School. He graduated from the Department of Western Art at Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1927 and participated in the Yeoran and Dongmi alumni groups. He organized a Drawing Exhibition with Gu Bonung and Lee Haeseon in 1931. After Independence, he participated in the National Art Exhibition as a judge from 1946 to 1961 and became a member of the Republic of Korea's National Academy of Arts in 1957. His works were based on the Classicism and Academism that he learned at Tokyo School of Fine Arts. His work was characterised by regular compositions and warm colors. In his early years, he mainly produced portraits, but he switched to softly painted still life subjects, such as flowers or Korean white porcelain objects mid-career. During his late career he created realistic works presenting Oriental philosophy as he saw it embodied within historically significant landscapes. To Sangbong achieved significant influence in Korea thanks to his gentle translation of the Western Academic tradition.