Dangu Art Exhibition commemorating the March First Independence Movement, 1946, MMCA Art Research Center Collection Collection, Gift of Kim Boggi

Dangu Art Academy

* Source: Multilingual Glossary of Korean Art. Korea Arts Management Service

Related

-

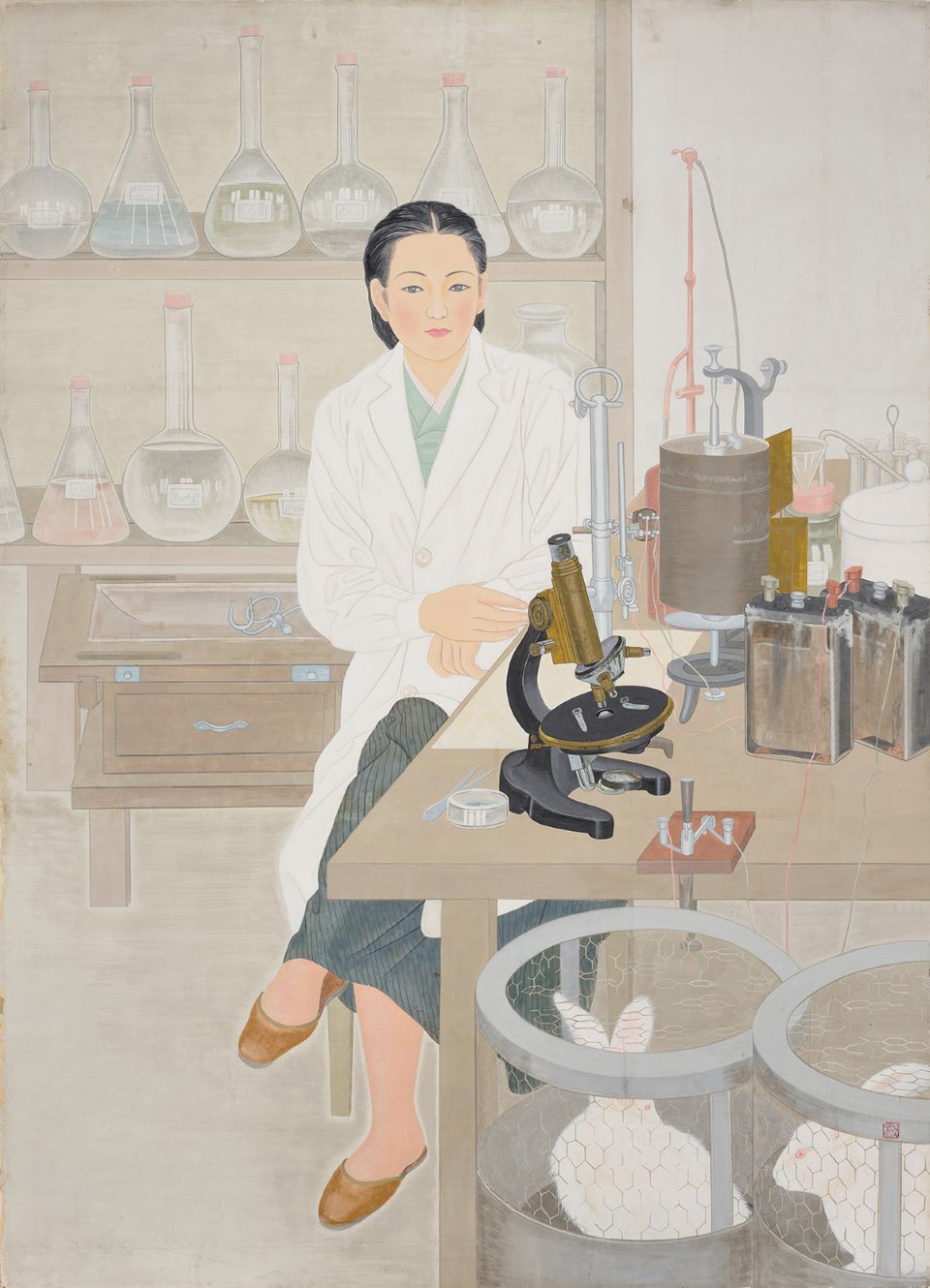

Lee Yootae

Lee Yootae (1916-1999, pen name Hyeoncho) learned painting from Kim Eunho in 1935 and participated in Husohoe, a group of Kim Eunho’s trainees, in 1936. He moved to Japan in 1938 to study at Kawasaki Ryuich’s art studio at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. He showed his potential by winning the government's general award and the Changdeokgung Palace award at the Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] in 1943 and 1944, and then worked as a professor at Ewha Womans University from 1947 to 1979. He played a pivotal role in modern Korean painting Academism by holding various positions, such as a Noteworthy Artist at the 1955 National Art Exhibition, Invited Author, judge, and a member of the National Academy of Arts. He was also a main member of Paek Yang Painting Association from 1957 to 1975. After his studies in Japan, he excelled at female figure paintings by combining the realism of Western paintings, a classical academicist Estern painting technique, and the bright colors together. He was specially known for his female figures described, which were described as idealised representations of the modern era. After independence, he created grand landscape paintings depicting the natural beauty of Korea. By doing so, he demonstrated the value of a traditional approach to landscape painting using real scenery.

-

Chang Woosoung

Chang Woosoung (1912-2005, pen name Woljeon) and studied Eastern painting at Kim Eunho's art studio, Nakcheongheon Studio in the 1930s. He joined Husohoe, Kim Eunho’s trainee group, in 1936. He was selected for the Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] from 1941 to 1944 and became a Noteworthy Artist. After independence, he worked as a professor of the Department of Oriental painting at Seoul National University from 1946 to 1961 and Hongik University from 1971 to 1974. He served as a judge, Invited Artist, and committee member at the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) and was a member of the National Academy of Arts, Republic of Korea. He played a pivotal role in developing the influence of the national academy within modern Korean painting. Prior to independence, his work focused on female figures based on the figurative style of western painting combined with traditional coloring methods. After independence, he tried to develop a mode of modern literati paintings (muninhwa). He emphasized the 'capturing the spirit' of literati painting in terms of succinct description, using simple yet strong ink lines, and light colors in his figure and flower-bird paintings. His work strongly influenced the critical approach to art in late twentieth century Korea.

-

Lee Ungno

Lee Ungno (1905-1989, pen name Goam) was born in Yesan, Chungcheongnam-do where he studied classic Chinese. He moved to Seoul in 1922 to study bamboo ink-painting from Kim Kyujin and was selected for the Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe]. In 1935, he attended Kawabatawa Art School and the Hongo Western Painting Center to study oil painting and learned Japanese realism from Matsbayasi Keiketsu. He returned to Korea in 1945 and produced realistic colored ink-wash paintings, such as the March 1st Independent Movement and Yungchayungcha. He pursued a style of semi-abstract art that attempted to express the inner spirituality. In the 1950s, he taught at Hongik University and Sorabol Art College. He moved to Europe after his exhibition in 1957 and created the letter-abstract genre that combines Western abstract art and East-Asian ink-wash painting. Diverse art critics, such as Jacques Lassaigne and Michel Tapie, praised his work, which led to several exhibitions in Europe, the U.S., and Japan. He opened the Oriental Painting Academy in Paris to teach ink-wash painting and received an honorary grand prize at the San Paulo biennale in 1965. Upon return to Korea he was imprisoned for two years because of the 1968 East-Berlin Affair and later moved to Paris to exhibit his works in Europe, the U.S., and Japan. In the 1980s, he created an ink-wash painting work depicting the people of the Gwangju Uprising. He passed away two days before a retrospective exhibition was held in 1989 in Seoul.

Find More

-

Eastern painting

Eastern painting (dongyanghwa) refers to the overall body of works created using traditional East Asian materials and methods, in contrast to Western painting. In Korea, Byeon Yeongro’s essay “On Eastern Painting” published in Dong-A Ilbo on 7th, July, 1920 was the first use of the term. The term then began to be used in Japan first to distinguish Oriental style paintings from Western ones. Until the late Joseon era, both calligraphy and painting were categorized under the term seohwa, but during the Japanese occupation of Korea in 1922, the first Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] divided the painting section into Western and Eastern styles. Thereafter, the term Eastern-style painting entered official use in the country. After independence, the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) continued to use the term “Eastern painting,” but since 1970, numerous arguments were made to replace it with "Korean painting," because the term was imposed unilaterally during the Japanese colonial era.

-

hangukhwa

A type of painting created during the 20th century that uses traditional Korean materials, techniques, and styles. The term emerged from the criticism that traditional-style paintings were called Eastern paintings in Korea, in contrast to China, where they were called national-style paintings, and Japan, where they were called Japanese-style paintings. The term hangukhwa (Korean Painting) entered official use following the overhaul of the educational curriculum in December 1981, and the appearance of the term Korean painting, with the subcategories ink wash painting [sumukhwa] and ink and light-colored painting [damchaehwa] were listed in art textbooks from 1983. The Grand Art Exhibition of Korea also began using the term hangukhwa (Korean Painting), as opposed to Eastern painting, in 1982. Prior to this, Hankukhwahui (Korean Painter’s Association) was used as a collective term for such Korean painters in 1964 and Kim Youngki (pen name Chunggang) argued to use the term Korean painting to define national identity in his essay “On hangukhwa (Korean Painting) and Criticism.” Criticism that Korean paintings, unlike the national paintings of China and Japan, do not have a narrative theme, and that the use of such a term was contrary to contemporary artistic trends, resulted in the term “hangukhwa (Korean Painting)” failing to achieve mainstream use. Hangukhwa (Korean Painting) is currently used interchangeably with the term Eastern painting.

-

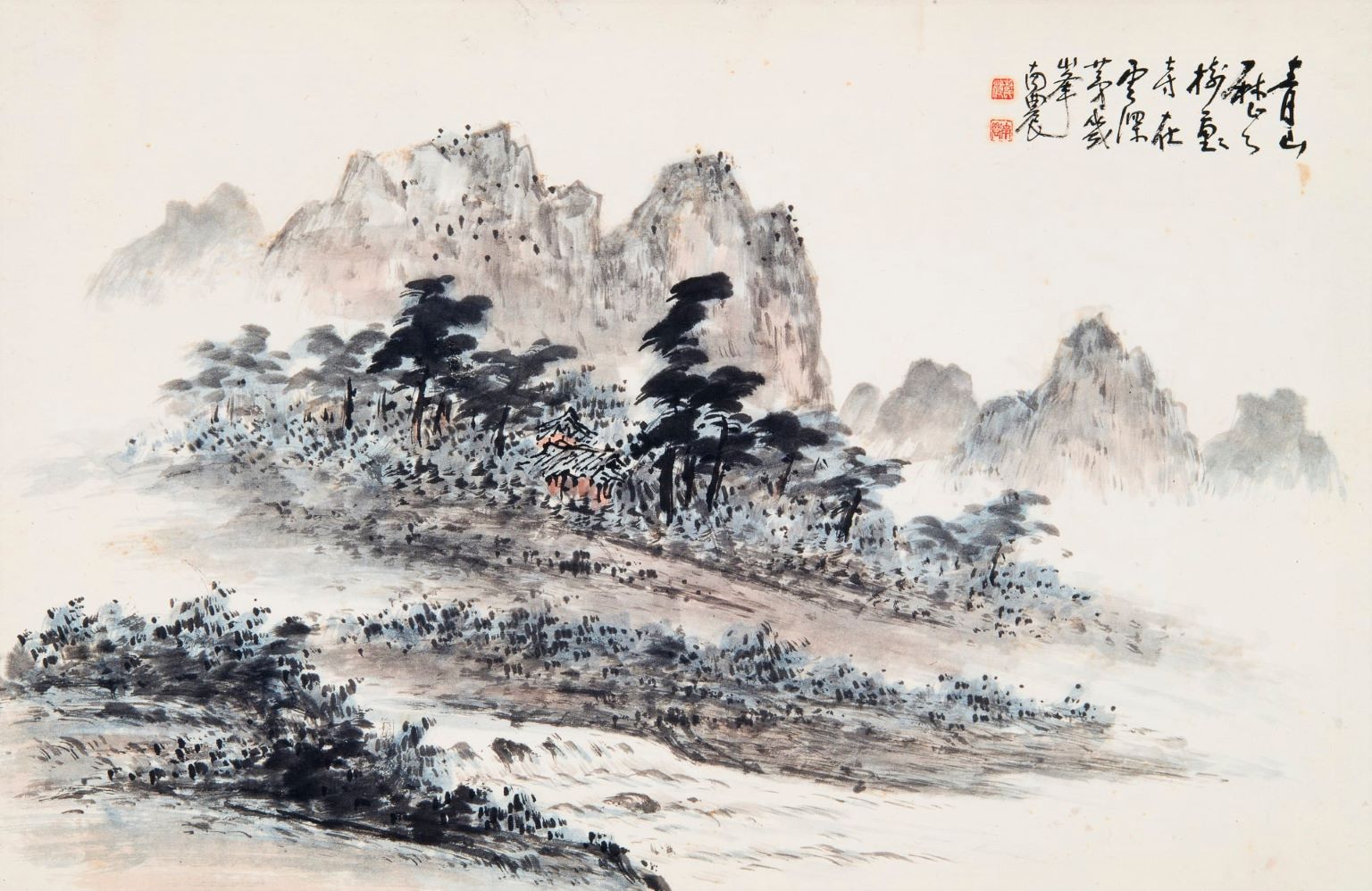

Bae Ryeom

Bae Ryeom (1911-1968, pen name Jedang) began his training in Oriental painting at the Lee Sangbeom’s Cheongjeon Art Studio in 1929 and became one of the representatives of the Cheongjeon Art Studio, winning special awards at the 1936 and 1943 Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe]. He joined the Cheongjeon Art Studio Exhibition from 1941 to 1943. He participated in the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) as a recommended artist after its establishment in 1949 and served as a judge in the Oriental painting division at the National Art Exhibition. He hugely influenced the Korean Oriental art community of the time, and his “Jedang style” became a term to describe certain ink landscape painting styles in Korea. He was selected as a member of the Republic of Korea's National Academy of Arts in 1954 and taught at the College of Fine Arts at Seoul National University and Hongik University from 1965 to 1968. In his early period, he emulated his mentor’s style and created ink paintings with dreamlike local scenes. In the 1940s, he developed his own style while painting Geumgang Mountain. After independence, he paid more attention to the concept and form of traditional landscape paintings and produced Namjong literati style ink landscape paintings.