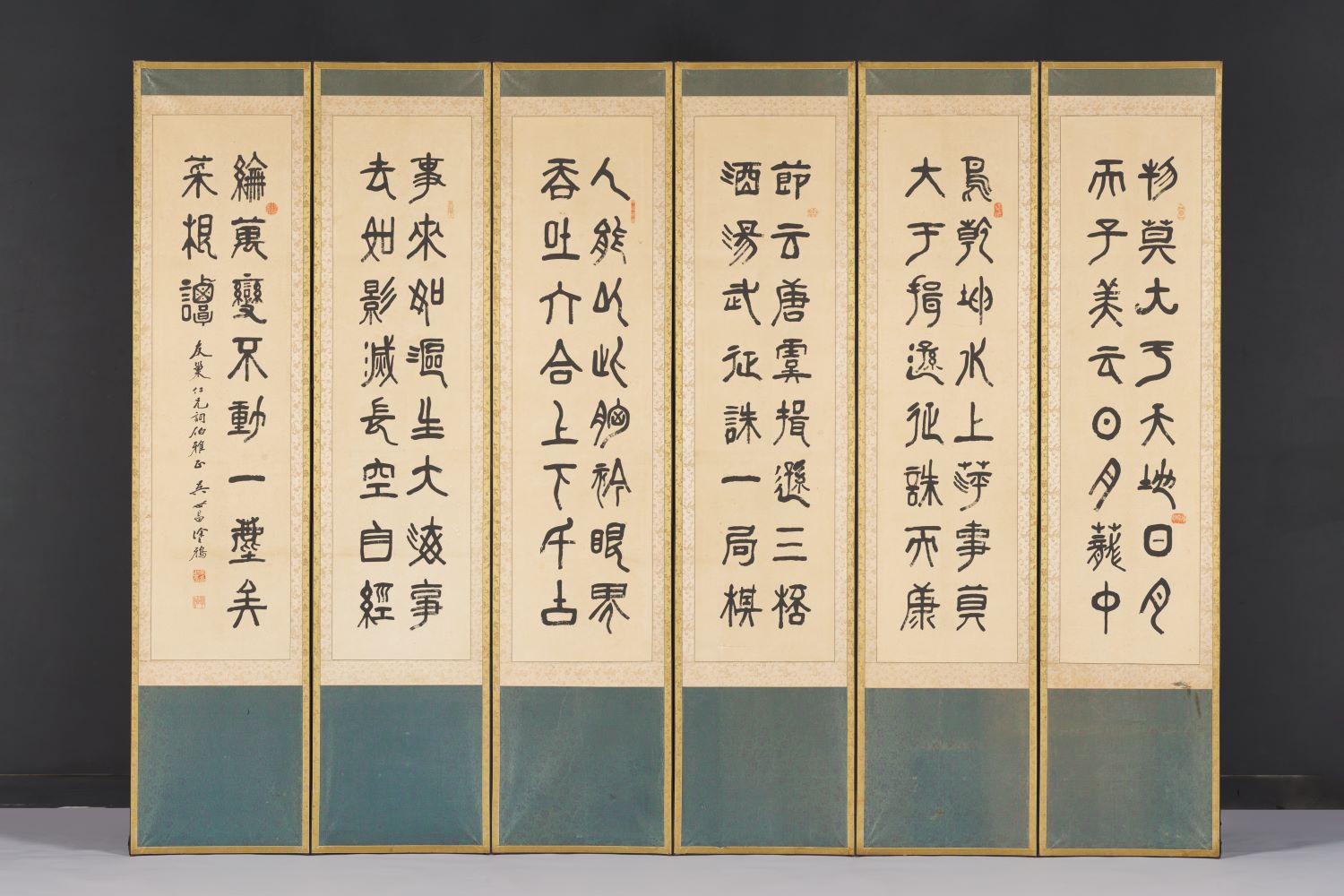

Son Jaehyeong, Ode to choong-moo gong, 1954, Ink on paper, 121×58cm. MMCA collection

Korean Calligraphy and Painting Association of Peers

* Source: Multilingual Glossary of Korean Art. Korea Arts Management Service

Related

-

Kim Eunho

Kim Eunho (1892-1979, pen name Yidang) joined the Calligraphy and Painting Society (Seohwa misulhoe) in 1912 and learned Oriental painting under An Jungsik and Cho Seokjin. He was known for his sophisticated brush strokes and attention to detail. Early in his career he was appointed as a court portrait painter. He produced several portraits of kings from the Joseon dynasty and gained a reputation for his portraits and colored figure paintings. He contributed his works to the first exhibition of the Calligraphy and Painting Association (Seohwa hyeophoe) and the Joseon Art Exhibition. His trainees organized Husohoe in 1936, which contributed enormously to the Modern Oriental Art community in Korea. However, he was accused of pro-Japanese activities due to his overt acquiescence to Japanese Imperialism and his involvement in its wartime propaganda. He tried his hand at ink paintings in the 1950s and experimented with modernized colored landscape painting from the 1960s into his later years. In the 1960s, he painted several portraits of historic figures and published Hwadanilgyeong (1968) and Seohwabaeknyeon (1977).

-

Kim Yongjin

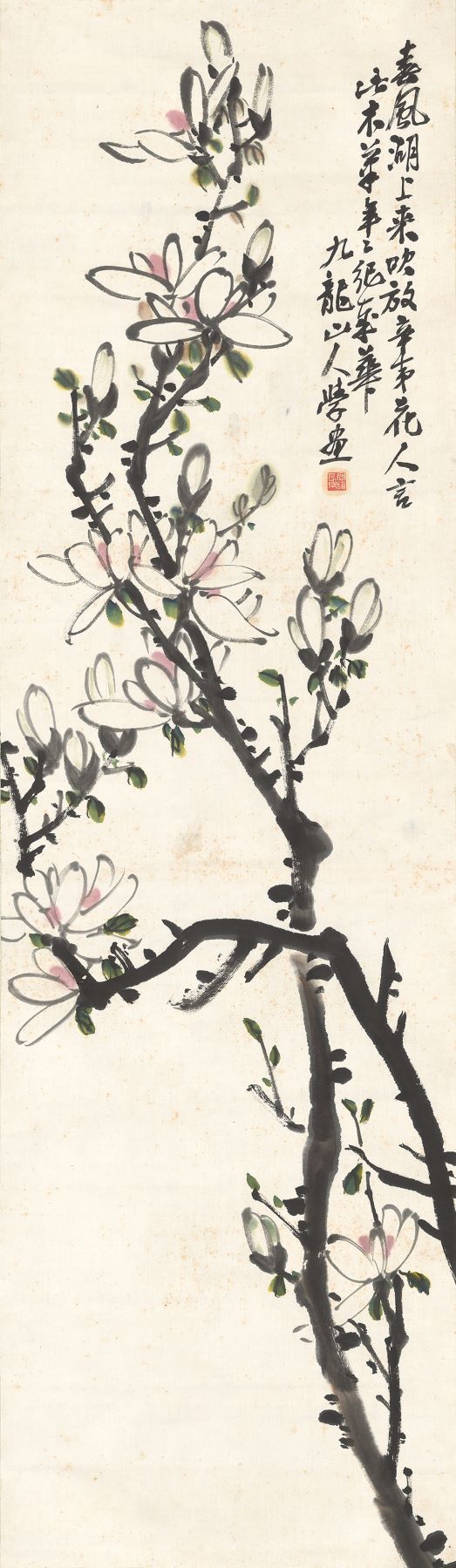

Kim Yongjin (1878-1968, pen name Yeongun or Guryongsanin) was appointed as a guard of a prince, a military officer’s ninth-class position, and later in his career rose to a second-class position. However, he retired early to focus on his art, which included traditional ink style calligraphy, four gracious plants paintings, and literati painting. His calligraphy and four gracious plants paintings were selected for the first to third Joseon Art Exhibitions [Joseon misul jeollamhoe]. He consistently submitted his works to the Calligraphy and Painting Association [Seohwa hyeophoe] as a member. He served as a judge of the Calligraphy Division from the first to the sixth National Art Exhibitions (Gukjeon), was a president of the Oriental Calligraphy Institute, and won a Seoul City Culture Award. Kim Yongjin was also a prominent collector of Painting and Calligraphy during and was skilled at Anjingyeong style regular script, clerical script, and semi-cursive script. His Indian ink orchid paintings emulated the style of Min Yeongik. He began drawing fruit and flower paintings, such as peonies, magnolias, and pomegranates after being influenced by Shanghai literati flower paintings in the late 1920s.

-

No Soohyun

No Soohyeon (1899-1979, pen name Shimsan) learned painting from An Jungsik and Cho Seokjin at the Calligraphy and Painting Society (Seohwa misulhoe) and graduated in 1918. In 1920, he participated in a series of decorative paintings at Changdeokgung Palace, and the resulting mural of Joilseongwando is his work. In 1923, he co-founded the art group Dongyeonsa with Lee Yongwoo, Lee Sangbeom, and Byeon Gwansik. Even though this group attempted to explore new, non-traditional possibilities for Eastern painting, their association did not last long. During the 1920s, he participated in the Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] and was the first artist to contribute editorial cartoons to the Choson Ilbo from 1924 to 1927. In the 1930s, he stopped participating in the Joseon Art Exhibition. Instead, he dedicated himself to exploring landscape painting based on his real experience of scenery and later established a new landscape painting style that incorporated the motif of oddly formed rocks and strangely shaped stones. Mountain Village (1956), Gyesanjeongchwi (Atmosphere of Valley and Mountain) (1957), Hongyeam (1961), and Paradise (1968) are considered his most representative works. He served as a judge and editorial board member of the National Art Exhibition and educated a variety of contemporary Eastern-style painters as an art professor at Seoul National University.

Find More

-

Lee Ungno

Lee Ungno (1905-1989, pen name Goam) was born in Yesan, Chungcheongnam-do where he studied classic Chinese. He moved to Seoul in 1922 to study bamboo ink-painting from Kim Kyujin and was selected for the Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe]. In 1935, he attended Kawabatawa Art School and the Hongo Western Painting Center to study oil painting and learned Japanese realism from Matsbayasi Keiketsu. He returned to Korea in 1945 and produced realistic colored ink-wash paintings, such as the March 1st Independent Movement and Yungchayungcha. He pursued a style of semi-abstract art that attempted to express the inner spirituality. In the 1950s, he taught at Hongik University and Sorabol Art College. He moved to Europe after his exhibition in 1957 and created the letter-abstract genre that combines Western abstract art and East-Asian ink-wash painting. Diverse art critics, such as Jacques Lassaigne and Michel Tapie, praised his work, which led to several exhibitions in Europe, the U.S., and Japan. He opened the Oriental Painting Academy in Paris to teach ink-wash painting and received an honorary grand prize at the San Paulo biennale in 1965. Upon return to Korea he was imprisoned for two years because of the 1968 East-Berlin Affair and later moved to Paris to exhibit his works in Europe, the U.S., and Japan. In the 1980s, he created an ink-wash painting work depicting the people of the Gwangju Uprising. He passed away two days before a retrospective exhibition was held in 1989 in Seoul.

-

Lee Sangbeom

Lee Sangbeom (1897-1972, pen name Cheongjeon) learned painting from An Jungsik and Cho Seokjin at the Calligraphy and Painting Society [Seohwa misulhoe] and graduated in 1918. He became a member of the Calligraphy and Painting Association [Seohwa hyeophoe] founded in 1918 and submitted his work to the first Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] in 1922. He repeatedly won special prizes and was appointed as a Noteworthy Artist and Participating Artist of Eastern painting in the Joseon Art Exhibition. In 1920, he participated in the Changdeokgung Palace mural project and created the work Samseongwanpado. He founded the Cheongjeon Art Studio to educate art students in 1933 and gained notoriety by contributing illustrations to serialized pro-Japanese newspaper novels. After independence, he was accused of being pro-Japanese, but continued to focus on his art nonetheless, becoming an important figure in art circles. In the 1950s, he created his own original ‘Cheongjeon’ style. This Korean-style landscape ink wash painting was based on real Korean scenery and represented what many consider as the essential aesthetics of Korean landscape painting. While he consistently participated in the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon), he never hosted a solo exhibition of his own, and in terms of his teaching in the post-independence period he taught as an art professor at Hongik University.

-

Oh Sechang

Oh Sechang (1864-1953, pen name Wichang) was an independence activist, calligrapher, journalist, and collector. Born in a family of influential Chinese-language interpreter-officials at the end of the Joseon period, Oh became one himself at the age of twenty. In 1886, he was appointed as a clerk at the Office of Culture and Information, where he also served as a reporter for Hanseong Sunbo newspaper. Later, he worked as president for Mansebo newspaper and Daehan Minbo newspaper. He joined the March First Independence Movement as one of the thirty-three national representatives. His deep interest in calligraphy and painting led him to participate as a promoter when the Calligraphy and Painting Association [Seohwa hyeophoe], the first artist organization in Korea, was established in 1918. After being jailed for his participation in the March First Independence Movement, Oh engrossed himself in collecting paintings and calligraphic works as well as writing about art history. Among his publications are Geunyeok insu (Seals of Korea) (1930–1937), a collection of Korean calligraphers and painters from the Joseon Dynasty to the then-present day; Geunyeok seohwi (A Collection of Korean Calligraphy) (1911) and Geunyeok hwahwi (A Collection of Korean Paintings), both of which are compilations of old paintings and calligraphic works that Oh collected; Geunyeok seohwajing (Biographical Dictionary of Korean Calligraphers and Painters) (1928) that compiles achievements of and criticism on Korean calligraphers and painters; Geunmuk (Korean Ink) (1943) that contains handwritings from the Goryeo Dynasty through the modern era; and Geunyeok seokmun (Korean Inscriptions), a compilation of rubbings of inscriptions on stone or metal from the Silla Kingdom through the Joseon Dynasty. As a calligrapher, Oh was well versed in seal and clerical scripts. He created distinctive calligraphic works that combined the shapes of ancient roof tiles, bronzeware, coins, and inscriptions on oracle bones with calligraphy. He was also a respected connoisseur of calligraphy and painting, which led him to play a key role in organizing exhibitions of ancient calligraphy and painting during the Japanese colonial period.