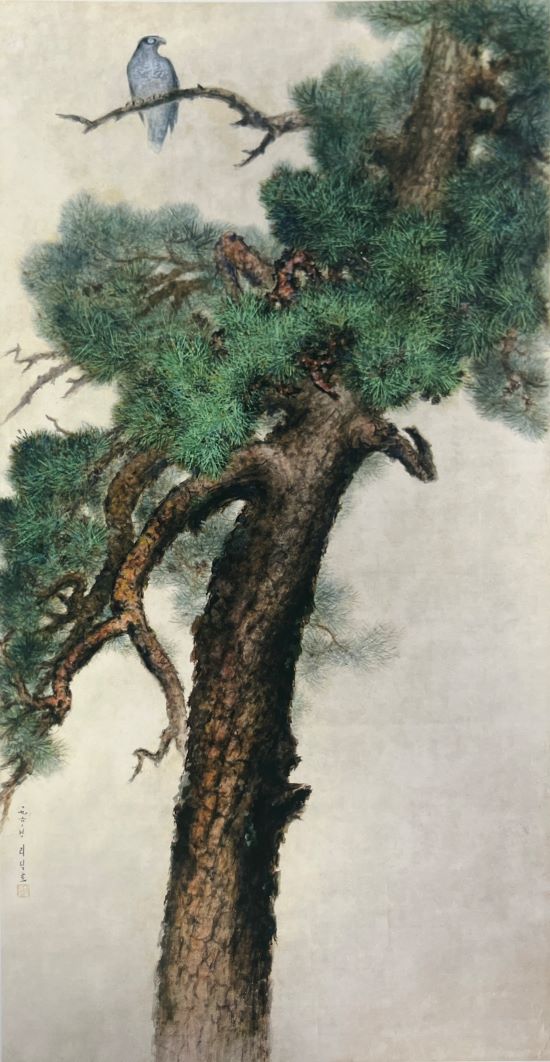

Lee Seokho, A Pine Tree, 1966, Ink and color on paper, 253×131cm. Korean Art Museum (2008), 39.

Lee Seokho

* Source: MMCA

Related

-

Kim Eunho

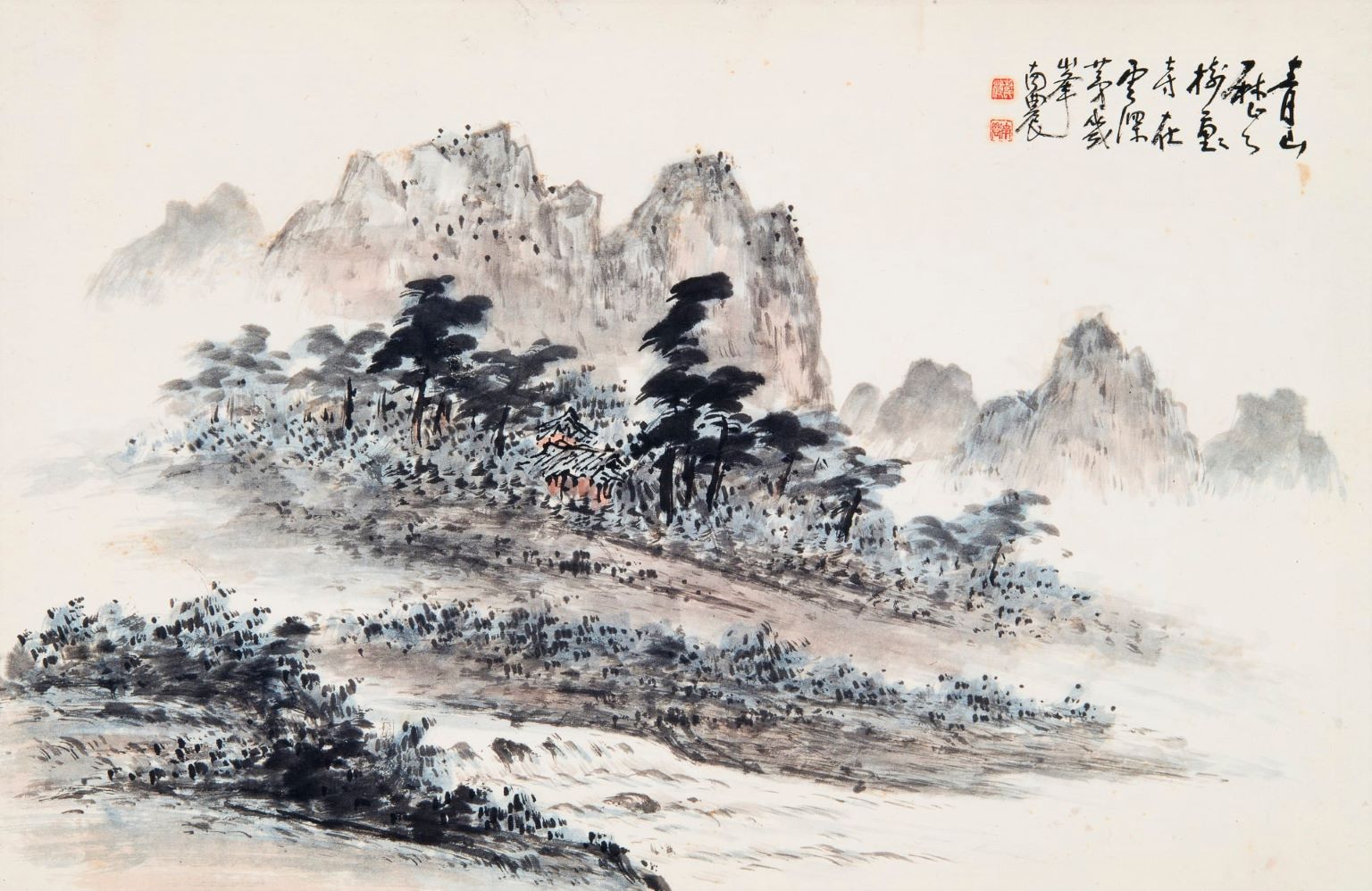

Kim Eunho (1892-1979, pen name Yidang) joined the Calligraphy and Painting Society (Seohwa misulhoe) in 1912 and learned Oriental painting under An Jungsik and Cho Seokjin. He was known for his sophisticated brush strokes and attention to detail. Early in his career he was appointed as a court portrait painter. He produced several portraits of kings from the Joseon dynasty and gained a reputation for his portraits and colored figure paintings. He contributed his works to the first exhibition of the Calligraphy and Painting Association (Seohwa hyeophoe) and the Joseon Art Exhibition. His trainees organized Husohoe in 1936, which contributed enormously to the Modern Oriental Art community in Korea. However, he was accused of pro-Japanese activities due to his overt acquiescence to Japanese Imperialism and his involvement in its wartime propaganda. He tried his hand at ink paintings in the 1950s and experimented with modernized colored landscape painting from the 1960s into his later years. In the 1960s, he painted several portraits of historic figures and published Hwadanilgyeong (1968) and Seohwabaeknyeon (1977).

-

Eastern painting

Eastern painting (dongyanghwa) refers to the overall body of works created using traditional East Asian materials and methods, in contrast to Western painting. In Korea, Byeon Yeongro’s essay “On Eastern Painting” published in Dong-A Ilbo on 7th, July, 1920 was the first use of the term. The term then began to be used in Japan first to distinguish Oriental style paintings from Western ones. Until the late Joseon era, both calligraphy and painting were categorized under the term seohwa, but during the Japanese occupation of Korea in 1922, the first Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] divided the painting section into Western and Eastern styles. Thereafter, the term Eastern-style painting entered official use in the country. After independence, the National Art Exhibition (Gukjeon) continued to use the term “Eastern painting,” but since 1970, numerous arguments were made to replace it with "Korean painting," because the term was imposed unilaterally during the Japanese colonial era.

-

Korean Artist Federation

An organization formed in February 1946 under the leadership of Kim Jukyung, Lee Insung, and Oh Chiho, who had recently left the Korean Art Association (Joseon misul hyeophoe). Additionally, numerous members of the Korean Art Alliance (Joseon misul dongmaeng) also joined the organization. The president of the Korean Art Association, Ko Huidong, became a member of the Citizens Emergency Council, a group closely aligned with Rhee Syngman, despite his claims to political neutrality. This drew criticism from the artists of the Korean Artists Association and provided the impetus for the establishment of the Korean Artist Federation (Joseon misulga dongmaeng). The governing body was the Central Executive Committee, which oversaw seven departments: the Painting Department, Art Critique Department, Children’s Art Department, Art Education Department, Performing Arts Department, Sculpture Department, and Crafts Department. The organization followed a five-point doctrine: First, eliminate the remnant influences of the Japanese Empire; second, reject all nationalistic and decadent artistic trends; third, establish a new movement of national art; fourth, form a partnership with the international art community; and fifth, attempt to achieve enlightenment of the general population through art and the education of future artists. The inaugural exhibition was from June 24 to June 31, 1946, at the Hwasin Gallery. In addition to exhibitions, the group also engaged in the production of promotional art, such as posters for the Democratic People’s Front.

Find More

-

Chung Chong-yuo

Chung Chong-yuo (1914-1984, pen name Cheonggye) enrolled in Osaka School of Fine Arts (Osaka Bijutsu Gakkō), and learned Japanese painting from Yano Kyōson after taking night classes briefly at Taiheiyo Art School in Japan. He became known in Korean painting circles by receiving an honorable mention with his Suburbs in Autumn at the Joseon Art Exhibition [Joseon misul jeollamhoe] in 1935. In 1939, he won the Changdeokgung Prize with Snow in March, and in 1940, he was awarded a special prize for Morning at Seokguram Grotto without review from a panel of judges. At the time he went back and forth to Seoul to study under Lee Sangbeom. He matured the plein-air landscape manner by adding the beauty of ink and brushwork in traditional painting to the Nanga (Southern painting) style he learned in Japan. He was well versed in bird-and-flower painting and figure painting and produced paintings in various formats, including a temple mural as seen in Portrait of Queen Seondeok at Buinsa Temple, and gwaebul (large hanging scrolls hung for outdoor rituals) such as Uigoksa Gwaebul. At the end of the Japanese colonial era, he created paintings reflecting the times. These paintings include State Protector King Geumgang Gongmyeong, Waiting for a Transport Ship, and Always Prepare Yourself As If You Were in a Battle Field. After Korea’s liberation from Japan, Chung Chong-yuo served as the head of the Ink painting section at the Korean Plastic Arts Federation [Joseon johyeong yesul dongmaeng] and the Korean Art Alliance [Joseon misul dongmaeng]. In 1946, he submitted his Procession on August 15 to the first Korean Art Alliance Exhibition and won the Democratic National Front Award. In 1948 and 1949, he enthusiastically engaged in artistic activities by holding solo exhibitions, where he presented Korean paintings that captured natural landscapes and social realities in a contemporary manner. However, immediately after the Korean War, he defected to North Korea. In North Korea, Chung was a member of the Korean Artist Federation [Joseon misulga dongmaeng] and worked as a professor at the Pyongyang Art University. He wrote art textbooks, such as Chaesaekhwae daehayeo (About color painting), Mukhwae daehayeo (About ink painting), Joseonhwa gibeop (Chosonhwa painting techniques), and Joseonhwa jaeryoe daehan sayongbeop (How to use Chosonhwa painting materials). He earned the titles “Laudatory Artist” in 1974 and “People’s Artist” in 1982 in recognition of his contributions to the establishment of North Korea’s Chosonhwa painting theories and the creation of related art works. Among his notable works are Gwaebul at Uigoksa Temple (1983, National Registered Cultural Heritage No. 614), Morning Clouds on Jirisan Mountain (1948), Farming Village in May (1956), and The People in Kosong Assisting the Front (1958).

-

Lee Yeosung

Lee Yeosung (1901-?, pen name Cheongjeong) was an independence activist, painter, politician, and journalist. His real name was Lee Myeonggeon. After graduating from Jungang High School in 1918, he lived in China. When the March First Independence Movement occurred in 1919, however, he returned to Korea and was involved in the anti-Japanese movement. He later went to Japan and enrolled in Rikkyo University in Tokyo. While serving as a member of the socialist organization Bukseonghoe which he formed in 1923 with Kim Jongbeom, Song Bongu, and Byeon Huiyong, Lee defected to China in 1926. After returning to Korea in 1929, he joined the Chosun Ilbo newspaper company in the following year as a reporter. There, he worked as head of the social affairs department and investigation department, and at the same time he was engrossed in studying ancient art. Lee Yeosung, who studied painting almost entirely on his own, held a two-person exhibition with Lee Sangbeom (pen name Cheongjeon) in 1935. In 1936, he contributed in serial form a writing entitled Traveling to Sinmido Island with illustrations in Chosun Ilbo newspaper. In 1944, he joined the anti-Japanese secret society Alliance for Founding a Nation [Geonguk dongmaeng] founded by Yeo Unhyeong, and after Korea’s liberation from Japan he served as a member of the Socialist Labor Party. After defecting to North Korea in 1948, Lee published books and articles, including Joseon misulsa gaeyo (A summary of Korean art history, 1955). In 1957, he served as a professor at Kim Il Sung University. The first research book on the history of Korean clothing, Joseon boksikgo (Examination of Korean clothing), which he wrote in 1946, is significant in that it suggests methodologies for studying clothes and defines the genealogy of Korean clothes. Lee Yeosung enjoyed painting realistic landscapes [sagyeong sansu] based on real scenery. From 1936 onward, he produced a vast body of historical paintings, most of which have been lost. He exerted a considerable artistic and ideological influence upon his younger brother Lee Qoede.

-

Artists who defected to North Korea

Artists who defected to North Korea refer to artists who moved their spaces of artistic activities to north of the armistice line during the period immediately after Korea’s liberation from Japan on August 15, 1945 until the signing of the truce agreement. Prior to the lifting of the bans on artists who were abducted by or defected to North Korea in 1988, they were labeled traitors for “betraying the South Korean system and choosing the North Korean one” or “choosing communism.” Their works were deemed “detrimental to ideas,” so it was forbidden to mention them. However, contrary to the reasons for restrictions imposed by the government, recent studies have revealed that the defection of most artists to North Korea resulted not from ideological choices or alignment with political system of North Korea, but from unavoidable circumstances caused by the war and division of the country. Accordingly, the scope of research on artists who defected to North Korea can vary depending on researchers or research environments. It discusses the conflict and movement between the two spaces of Seoul and Pyongyang or South and North Korea and further includes those that the South Korean government defined as artists who chose the North Korean system. The number of artists who defected to North Korea amounts to roughly sixty to eighty. In recent years, there has been a view that the so-called consecutive lifting, which differentiates and selectively relieves artists who defected to North Korea voluntarily, those abducted to North Korea, those residing in North Korea, and those who returned to North Korea after defection to South Korea, is an act of high-level public security control. This is seen as a non-academic power tyranny and violence against intelligence that insults the particularity of art, leading to voices to dismantle and prospectively reconstruct the existing frame of the lifting of bans on abducted artists and artists who defected to North Korea.